Susan Farquharson, Executive Director, Atlantic Canada Fish Farmers Association

Professor Ann Dale, School of Environment & Sustainability, Royal Roads University

Published March 31, 2016

Case Summary

The implementation of Integrated Community Sustainability Plans (ICSPs) has varied tremendously across the country. Many have been implemented directly by individual communities, while other provinces, notably British Columbia and New Brunswick have adopted a provincial coordinating role for the distribution of the federal gas tax funds. This case study explores what worked and didn’t work in the province of New Brunswick.

Municipal planning processes in New Brunswick are mandated by provincial policies with a focus on infrastructure. Even without the flexibility to plan individually, however, local governments in New Brunswick to varying degrees have incorporated the imperatives of sustainability within their planning processes. These processes may not be as formal as an Integrated Community Sustainability Plan would advocate, signifying a more relevant solution to advancing municipal sustainability might be a sustainability planning framework that creates the capacity for local ownership and management. Removing the hierarchical governance barriers currently limiting the implementation of municipal sustainability planning in New Brunswick is a critical first step.

Sustainable Development Characteristics

More than 30 years after the Brundtland Commission the implementation of sustainable development locally remains challenging for some communities, as seen in the New Brunswick case studies. Evaluating sustainable development at a municipal scale remains a challenge in most if not all regions of the world (Sustainable Cities International, 2012). This may be due to the problems associated with developing a common set of indicators that can be adopted and integrated into vertical and horizontal scales of policy that recognizes local complexities and the “needs of citizens” (2012, p. 4) in each municipality. There is also the challenge of determining data relevance, at these policy scales, for each community (Dale, Foon, & Herbert, 2011, p. 2).

Local government bodies, such as cities and municipalities, have the opportunity to provide leadership and advance sustainable development. Ling, Hanna, and Dale (2009) suggest that municipalities are the leaders, on the “front line of implementing sustainable community development” (p. 1) giving them the local capacity to drive sustainability. This places municipalities in the position to create “resilient and adaptable communities” (Dale, Foon, & Herbert, 2011, p. 7) on a case-by-case basis that defines sustainable development meeting individual community needs.

This case study explores the complexities of municipal planning processes and the attempts of four New Brunswick local governments to integrate the requirements of the Federal Government’s Gas Tax Funding Program initiated in 2005. It specifically explores the role that the first decade of the Gas Tax Funding Program (2005-2014) played in New Brunswick.

Previous research has demonstrated that to realize sustainable community development, municipal plans must be:

- integrated;

- long-term rather than short-term;

- implementation is dependent upon a community engagement process;

- measurable, and

- political accountability built into the plan’s life cycle.

In response to inquiries from small communities in B.C. when the Federal Government Tax Rebate Program was announced, an ICSP template was developed for local governments and their communities.

Community Contact Information

Professor Ann Dale

Trudeau Fellow Alumna (2004)

Canada Research Chair (2004-2014)

Royal Roads University

School of Environment & Sustainability

Faculty of Applied Social Sciences

2005 Sooke Road, Victoria, B.C. V9B5Y2

Tel: 250. 391-2600, x4117

rrutesting.com

What Worked

Although legislation was viewed as a barrier to municipal sustainability planning, there was generally support for the new asset management planning requirement to access the GTFP funds as “infrastructure in New Brunswick is old and in need of repair”, as noted by one interviewee. But, information also suggested that the gas tax funding distribution with only an infrastructure focus does not lead to integrated sustainability planning, emphasized by one interviewee stating that “it is not pipes in the ground, it is quality of life for people” which requires “flexibility to use it for non-infrastructure needs.”

What Didn’t Work

Even though municipalities are, on a case-by-case basis, attempting to incorporate sustainable development in their planning processes, they remain largely unintegrated in overall planning processes for each of the case study communities reviewed. One reason may be that the benefits of long-term collaborative participation and commitment of citizens and institutions to sustainable development planning processes through policy change, active engagement and allocation of resources needed to incentivize communities has yet to be recognized (Braun, 2007). Another reason may be that consultants were used to conduct both the regional plans in 2007 – 2009, incorporating sustainability as well as the ICSPs. Consultants are employed to achieve a plan within a set time and budget, which mitigates against the need for the time and resources required for meaningful community engagement and long-term commitment of citizens.

Still viewed as a challenge and a barrier, community engagement is seen as taking too long, too expensive with too many diverse perspectives and subsequent actions to be incorporated by those charged with developing and implementing final plans. Additionally, municipalities that do want to conduct more integrated local planning find their efforts once again strangled by outdated policies that require provincial oversight and permissions to complete, if started. This is evident even in the newly updated Municipalities Act (R.S.N.B, 2015) that still advocates provincial control over municipalities. Additionally, there is still a one-size fits all municipal plan outline developed at the province level, to which each municipality must adhere with little flexibility to meet local unique contexts.

More recently, the province implemented the Capital Investment Plan (CIP), an additional requirement of the Province and condition for receiving Gas Tax Funding. This research demonstrated that if municipal planning processes are dictated at the provincial level and this centralized control over planning processes continues, local sustainability planning and integration will not effectively occur. This runs counter to the increasing emphasis over the last decade on the criticality of place-based decision-making, which coupled with the province’s inflexible co-ordination has led to varying degrees and success in implementing ICSPs locally.

Detailed Background Case Description

In 2005, Canadian municipalities received an incentive to develop Integrated Community Sustainable Plans (ICSPs) when the Canadian Federal Government introduced the Gas Tax Funding Program (GTFP) (Canada-New Brunswick, 2005). As a Federal – Municipal Government policy instrument, the GTFP supported municipal level sustainability planning in the development of healthy and vibrant communities through the integration of economic, environmental, social and cultural sustainability objectives (Canada - New Brunswick, 2005).

The Gas Tax Funding Program required every municipality that received funds to develop an ICSP or similar document by March 2010 (Government of Canada, 2014). Additionally, recognizing the importance of public participation and a broader multi-stakeholder approach (Dale, Dushenko, & Robinson, 2012, p. 86), (Rametsteiner, Pulzl, Alkan-Olsson, & Frederiksen, 2011, p. 69), the GTFP required any plans developed to include public participation maximizing the benefits of setting and achieving sustainability objectives (Canada-New Brunswick, 2005).

The Province of New Brunswick signed a ten-year agreement 2005-2015 (Canada-New Brunswick, 2005) with the Government of Canada outlining the terms and conditions for accessing the Gas Tax Funding Program. Schedule H of that agreement described the requirement for Integrated Community Sustainability Plans (ICSP) noting them as “supporting the development of sustainable healthy and vibrant communities” (2005, p. 40). An additional clause in the agreement noted that in New Brunswick, ICSPs would be incorporated in existing planning processes such as Community Growth Strategies of each Community Economic Development Agency (p. 40).

The Gas Tax Funding Program

After years of lobbying by municipalities across Canada, the Gas Tax Funding Program (GTFP) was established in 2005. Administered by Infrastructure Canada, it currently provides two billion annually to provinces and territories responsible for allocating the funds to Canadian municipalities to help build and revitalize their public infrastructure assets (Government of Canada, 2014). To do so, incorporated areas develop projects locally and “prioritize them according to their needs” (Canada-New Brunswick, 2005, p. 2). The Government of Canada (2013) reported over 3,600 municipalities and 13,000 projects across Canada had benefited from the financial support and flexibility of the program since its inception in 2005. On April 1, 2009, the Government doubled Gas Tax Fund payments from $1 billion to $2 billion per year for Canada’s municipalities (Government of Canada, 2009). On December 15, 2011, federal legislation made the payments under the GTFP a permanent source of federal infrastructure support (Government of Canada, 2013, p. 173).

As the result of a program review (Government of Canada, 2009), municipalities are no longer required to develop an Integrated Community Sustainability Plan. Currently administrative agreements to access the GTF are developed based on the submission and approval of a provincially specified five-year Capital Asset Plan template outlining the priorities of the municipality. Each five-year plan must meet objectives set by the province including making progress on “improving Local Government planning and asset management” processes (Province of New Brunswick, 2015).

Integrated Community Sustainability Plans (ICSP)

The ICSP planning process was initiated across Canada as a requirement of the federal government when introducing the first round of Gas Tax Funding Program in 2005 (Canada-New Brunswick, 2005). Introduced to encourage communities to plan and develop action plans, the ICSP was a requirement of bilateral agreements between the Government of Canada and each province for Gas Tax Funding transfers.

To meet this requirement and receive transfers summarized in Figure 1, the Province of New Brunswick developed agreements with Community Economic Development Agencies to develop “Community Growth Strategies” that incorporated the principles of Integrated Community Sustainability Plans (Capital Management Engineering Limited, 2010, p. 13). Even though the Province funded these regional strategies, municipalities could still conduct an Integrated Community Sustainability Plan process, if they chose to find their own funds.

| Fiscal Year | Canada’s Contribution |

| 2005-2006 | $13,927,000 |

| 2006-2007 | $13,927,000 |

| 2007-2008 | $18,570,000 |

| 2008-2009 | $23,212,000 |

| 2009-2010 | $46,424,000 |

| Total | $116,060,000 |

Figure 1: Canada’s Total Gas Tax Contribution to New Brunswick 2005-2010

Note: Adapted from Agreement on the Transfer of Federal Gas Tax Revenues Under the New Deal for Cities and Communities, Schedule H – Integrated Community Sustainability Plans, p. 11 by Government of Canada and the Province of New Brunswick, 2005

In New Brunswick, the Gas Tax Funding allocations to the incorporated areas (e.g., villages, cities, rural communities) are determined on a per capita basis. Currently, as per the 2014 Canada New Brunswick Gas Tax Transfer agreement (Canada-New Brunswick, 2015), the allocations to municipalities described in Table 3 are dependent on the completion of a Capital Investment Plan (CIP). The template and requirements for the CIP are posted by the Department of Environment and Local Government staff on the provincial website (Province of New Brunswick, 2015). Once a plan has been submitted, evaluated and accepted by the Province an agreement contract is finalized with the Department of Environment and Local Government (Ibid, 2015).

The Minister of Environment and Local Government controls the allocation of Gas Tax Funds for the unincorporated areas (e.g., Local Service Districts) as defined in Table 3. This portion of the Gas Tax Fund is distributed on a regional basis and not a per capita basis. The province identifies regions that encompass the unincorporated areas of the province and funds are distributed within those regional boundaries on a project-by-project basis.

Table 3: New Brunswick Gas Tax Allocations 2014-2018

(Province of New Brunswick, 2014)

| Total Federal Transfer | $225,276,000 |

| 1.35% Admin to Province | $3,041,227 |

| Balance | $222,234,773 |

| 20% Unincorporated Areas Allotment | $44,446,955 |

| 80% Municipal Allotment | $177,787,818 |

| Total Distribution Amount | $218,267,600 |

Provincial Backdrop

In 1962, as a result of the New Brunswick Commission on Finances and Municipal Taxation’s assessment of municipal government (referred to as the Byrne Commission) (Province of New Brunswick, 2015) the province legislated a new Municipalities Act. This centralization, seen at the time to address the need for sustainable community development and provide equitable access to basic needs such as health and education, fundamentally changed the structure of rural administration in New Brunswick by abolishing the “County Councils” (2015) and establishing a new system under the authority of the Provincial Government.

In May 2007p the province commenced a series of pilot projects intended to promote sustainable community development as part of the New Brunswick Public Engagement Initiative and the agenda for achieving self-sufficiency by 2026 (Province of New Brunswick, 2008). Due in part to the results of those pilot projects, a New Brunswick Self-Sufficiency Task Force (The Self-Sufficiency Task Force, 2007, p. 36) suggested that the Government move quickly to implement the recommendations, that sent a message recognizing the need for transformative change, reinforced with the core imperatives of sustainable development. Contrary to the 1962 centralization of services, the messages received during the consultations suggested that decentralization and support of small communities was more sustainable. A key recommendation called for a comprehensive regional planning process for all areas of the province highlighting the environment, sustainable development, land use, housing infrastructure, and social and economic development. Coincidently, at the same time the Canadian Commission for UNESCO recommended new methods for engaging citizens as integral to any planning process. (Council of Ministers of Education-Canada, 2007).

In 2010, more than 30 groups across New Brunswick collaborated, without provincial or municipal government involvement, to develop the Green Print: Towards a Sustainable New Brunswick (New Brunswick Environmental Network, 2010). This was an action plan that contained goals and “green metres” to measure the progress of sustainability implementation by governments and others.

In 2012, provincial government literature described sustainable development as a “community that meets its present and future social, economic and environmental needs” with a tag line of “enough for everyone forever” (Province of New Brunswick, 2015, p. 2). This aligned with the Brundtland Commission’s original definition that sustainable development is meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Brundtland Commission, 1987). The provincial literature promoted planning processes and provided example table of contents for Integrated Community Sustainability Plans or Green Plans that indicated support for, but did not require, municipalities to plan and/or include sustainability principles of social equity, economic viability and environmental quality (2015, p. 3).

In 2012, Margaret Tusz-King (2012) reinforced, in her report “Local Government, Sustainability and Climate change: A Resource for Elected Municipal Officials in New Brunswick, the importance of local government as those closest to the people. As she reflected on climate change impacts, she noted that due to their community planning, emergency measures, provision of clean water and ability to understand the issues they were in the best position to govern the wellbeing of each community

More recently provincial planning staff have been promoting sustainable planning in a “Provincial Framework and Principles; Creating Sustainable Communities in NB” presentation (Province of New Brunswick, 2014) at conferences and workshops. Finally, communications accessed on the Government of New Brunswick website (Province of New Brunswick, 2015) reflect an enthusiastic promotion of citizen-based sustainability planning offering a toolkit that included an indicators fact sheet and referred users to one of the case studies used in this research, the City of Saint John.

The Government of New Brunswick has not required municipalities to develop an Integrated Community Sustainability Plan (ICSP) or a similar document as suggested in the Canada – New Brunswick Gas Tax Funding 2005-2014 agreement (Canada-New Brunswick, 2015) to access funds. As a substitute, the province used a portion of the Gas Tax Fund to employ consultants to work with the 15 Community Economic Development Agencies (CEDA) operating regionally in the province in 2006 (Province of New Brunswick, 2015). Consultants were tasked with incorporating sustainability principles in regional plans that encompassed unincorporated as well as incorporated (i.e., municipalities) areas.

Even though not a requirement to access Gas Tax Funding by the province, a number of municipalities have voluntarily completed an ICSP, see Table 1. As previously mentioned, each municipality had to find their own funds to conduct the ICSP planning process as resources to do so were not specifically allocated by the province in the Gas Tax Funding transfers to municipalities (Province of New Brunswick, 2015).

Table 1: List of Integrated Community Sustainability Plans and Green Plans in New Brunswick (Province of New Brunswick, 2015)

| Municipality | Plan Name |

| Alma | Vision Alma |

| Bouctouche | Un Plan Vert pour la Ville de Bouctouche |

| Cap-Pelé et Beaubassin-est | Une stratégie verte |

| Caraquet | Green Down Town Caraquet |

| Cocagne | Transition Town |

| Dieppe | 5 Year Green Plan |

| Fredericton | First to Kyoto |

| Grand Falls | Greening Grand Falls’ Town Services |

| Kedgwick | Kedgwick Green Plan |

| Memramcook | Le plan vert |

| Moncton | Adapting to the New Millennium |

| Petitcodiac | Petitcodiac and Area Sustainability Strategy |

| Port Elgin | Picture Port Elgin |

| Sackville | Sustainable Sackville |

| Saint-Isidore | Village of Saint-Isidore Green Plan |

| Saint John | Integrated Community Sustainable Plan |

| Saint-Léonard | Green Plan |

| Shippagan | Une vision …des actions |

Municipal Legislation

Canadian municipal legislation originates from legislation enacted in Upper Canada in 1849 (The Law Society of Upper Canada, 2015). That legislation, known as the Baldwin Act (2015), established the role, function and structure of local authorities in the British North American colonies. In 1867, the Canadian Constitution Act (SC, 1867) created provincial governments granting them responsibility for making rules related to municipal institutions. At that time, less than 20 per cent of citizens lived in municipal areas compared to the approximately 80 per cent today (Lidstone, D., 2004).

Section 92(8) of the Constitution Act delegates powers to the provinces respecting “municipal institutions in the province” (SC, 1867). Municipal authority to regulate use of land is a provincial power under the "property and civil rights" heading in Section 92(13) of the Constitution Act (SC, 1867). That delegation of land use planning to local governments is subject to powers retained by the provinces. Consequently, the laws controlling land use are primarily provincial, although there are exceptions created by federal control over land used for First Nation reserves, airports, railways, harbours and other purposes regulated by federal law (SC, 1867). New Brunswick has delegated minimal powers to local governments to control local matters but not concerning planning which remains in the control of the provincial government (R.S.N.B, 2015).

In 2011, the Province implemented the Regional Services Delivery Act (RSDA), proclaiming a new system of local governance in New Brunswick (Regional service delivery act; C- 37, 2012). Subsequently in 2012, there were 12 Regional Service Commissions (RSC) (Province of New Brunswick, 2015) created (See Map in Appendix 4). This replaced the District Planning Commissions (DPC) system that had been operating in the Province serving 98% of the land area of the Province and 69% of the citizens including all the unincorporated areas and 67 of the 101 municipalities (Bell, J., 2011). .

The 12 Commissions have five main objectives including strengthening the capacity of local governments while maintaining their community identity, increased collaboration, communication and planning between communities, and modernized legislation supporting local and regional decision-making (Province of New Brunswick, 2011). Their mandate includes regional planning, local planning in unincorporated areas, solid waste management, regional policing collaboration, regional sport, recreational and cultural infrastructure planning and cost sharing, as well as regional emergency measures planning (2011).

The Commissions, comprised of incorporated as well as unincorporated areas, were charged with ensuring communities receive services but were not assigned the legislated authority to tax for said services, in the Regional Services Delivery Act (R.S.N.B., 2012). The municipal members of the Commission have retained the authority to tax and continue to do so within their legislated boundaries (Telegraph Journal, 2014) to provide the services they are responsible for and given authority to manage in the Municipalities Act (R.S.N.B, 2015).

As a result, in New Brunswick there are three legislations directing municipal planning activities, the Municipalities Act (R.S.N.B, 2015), the Community Planning Act (R.S.N.B., 1973) and the Regional Services Delivery Act (R.S.N.B., 2012). Interestingly, the use of the term sustainable development, or some variation of, is not included in any of these policies.

Case Study Community Descriptions

City of Saint John

Located on the southern New Brunswick coast, Saint John is the largest city in New Brunswick. Incorporated in 1785, the city has a census metropolitan area (CMA) population of 127, 761 with 70,063 living within the city core (Statistics Canada, 2011). The population density per square kilometre is 38 on a total land area of 3,362.95 square kilometers.

Saint John has a median family income of $68,520 (Saint John, 2015). The primary occupations employing 56.6% of the labour force, are the sales and services, trades, transport and equipment operators, and business and finance sectors. Employment in the education, law and social, community and government and health sectors employ less than 20% of the labour force, and work in the natural resource sectors providing the lowest employment, approximately 2%.

Promoted as a ‘historically-rich and culturally diverse city’ (Saint John, 2015), in 2012 the city was named a Top 7 Intelligent Community by the Intelligent Community Forum (ICF) (Intelligent Community Forum, 2015), an international think-tank that studies the economic and social development of the 21st Century community. In 2010, the city was designated as a ‘Cultural Capital of Canada’ and in 2011 was named the winner of CBC Maritime's “Cultureville” contest. Contrasting these recent accolades, Saint John was most recently presented in the media as having one of the highest child poverty rates in Canada (Telegraph Journal , 2014).

Community services available in the city include a multi-modal public transportation system (i.e., bus, taxi), an international airport, two hospitals, a university and community college, and three recreational facilities (i.e. YM/WCA, Harbour Station, and Canada Games Aquatic Centre) as well as two municipal parks. Additionally, a multicultural centre is accessible providing integration services for immigrants.

City of Moncton

The City of Moncton known as the hub of the Maritimes (City of Moncton, 2015) has a census metropolitan area (CMA) population of 138,644 with 69,074 living within the city core (Statistics Canada, 2011). The population density per square kilometre is 489.3 within a land area of 2,406.31 square kilometers.

Moncton has a median family income of $71,290 (City of Moncton, 2015). The primary occupations, employing 58% of the labour force, are the sales and services, trades, transport and equipment operators, and business and finance sectors. Employment in the education, law and social, community and government and health sectors comprises 19.5% of the labour force, and work in the natural resource sectors providing the lowest employment >1%.

In 2009, Moncton was named a Top 7 Intelligent Community by the Intelligent Community Forum (ICF) (Intelligent Community Forum, 2015) . In 2008, Moncton was designated the ‘most polite and honest city’ by Readers Digest (Moncton, 2015). In 2014, the city was ranked as the lowest cost location for business in Canada (Moncton, 2015) by KPMG.

Community services available in the city include a multi-modal public transportation system (bus, taxi, and train), an international airport, two hospitals, two universities and two community colleges, and a downtown multi-use sports and entertainment centre in early development phase. Additionally, the city has developed an immigration strategy (City of Moncton, 2015) providing integration services for newcomers.

Town of St. Andrews

The Town of Saint Andrews was designated as a National Historic Site in 1998 (St. Croix Estuary Project Inc ~ Eastern Charlotte Waterways Inc., 2014, p. 23). With a population of 1,889 and a population density per square kilometre of 226.2 on a total land area of 8.35 square kilometers (Statistics Canada, 2011), it has a much higher density than the county average, in which the town is geographically located, 7.8 (2011). There is a significant seasonal flux in population due to the large number of residences owned by non-residents, as well as the students who take up residence during the academic year at the college, and who do not stay during the summer months (pers.comm, 2015).

St. Andrews has a median family income of $27,294 (Statistics Canada, 2011) The primary occupations, employing 55.6% of the labour force, are management, sales and service, trades, transport and equipment operators, and education, law and social, community and government services sectors. Employment in the arts, culture, recreation sport and health sectors employ less than 10% of the labour force, and work in the natural resource sectors providing the lowest employment >1%.

Community services available in the town include two primary schools, a community college, a recreational facility, as well as the Huntsman Marine Science Center, the Fisheries and Oceans - St. Andrews Biological Station, and the historic Algonquin Resort facilities (Town of St. Andrews, 2015). A regional multicultural centre located in an adjacent municipality serves the town (Charlotte County Multicultural Association, 2015). Additionally, the town is leading the development of a multi-modal transportation system to integrate bus- dial-a-ride- taxi systems, to connect the various county communities with essential services that are being increasingly centralized to larger municipalities (Hanson, 2014).

Village of Grand Manan

The Village of Grand Manan is an island community, located in the lower Bay of Fundy, accessible only by boat (two ferries service the island) and air. It was incorporated in 1995, as a single village, as a result of an island wide amalgamation of several small communities, most notably Seal Cove, that was designated a National Historic Site remaining relatively unchanged since the 19th century (St. Croix Estuary Project Inc ~ Eastern Charlotte Waterways Inc., 2014, p. 40). The island is 24 kilometres long and 11 kilometres wide (Village of Grand Manan, 2015) with a population of 2,377 and a population density per square kilometre of 15.8 within a land area 150.86 square kilometers (Statistics Canada, 2011).

Grand Manan has a median family income of $49,147 (Statistics Canada, 2011). The primary occupations, employing 62.1% of the labour force, are the natural resources, agriculture and related production sector, and the sales and services, trades, transport and equipment operators and related occupations. Employment in the education, law and social, community and government, and management sectors as well as the business, finance and administration sectors employ 25% of the labour force, and work in the health sector employing 5.9%.

Community services include a transportation system, ferry and airport (providing transportation to mainland areas), one hospital, a LEED certified community and recreational facility, and two privately operated parks.

Analysis

Provincial agreements with municipalities, requested during interviews with provincial staff, for the transference of Gas Tax Funding were not considered public and not accessible from the province for this research.

All case study communities had filed a current municipal plan with the Province in accordance with the Community Planning Act (R.S.N.B., 1973) at the time of this research, while only Saint John and Moncton had completed an ICSP (Province of New Brunswick, 2015).

The City of Moncton’s ICSP, Shaping Our Future: City of Moncton Sustainability Plan (An Integrated Sustainability Plan) (Dillon Consulting Limited, 2011) incorporated five community objectives (i.e., green, healthy, vibrant, prosperous and engaged), 24 goals and more than 75 indicators developed with environment as the “central pillar of sustainability” (2011, p. 2).

The City of Saint John’s Integrated Community Sustainability Plan (Dillon Consulting Limited, 2008) unlike Moncton’s, noted that sustainability was “about more than protecting the environment” (2008, p. 5) and incorporated “20-year goals and sustainability principles” under six elements of sustainability: social, cultural, economic, environment, infrastructure and governance (p. 7).

The same consultant developed both plans incorporating a community consultation process, which included online surveys and public meetings, as well as in the case of Saint John, two stakeholder workshops to develop objectives, actions, indicators and targets.

The Town of St. Andrews conducted a background analysis (Resource and Educational Consultants, 2009), which included a community consultation process before completing their municipal plan in 2010, with a purpose of providing policies and proposals to guide and control the economic, social and physical development of the town (Town of St. Andrews, 2010).

Grand Manan, the newest municipality incorporated in 1995, filed a Rural Plan in 2004 listing objectives to “balance development pressures, environmental integrity, and community identity” (Village of Grand Manan, 2004) as one of 42 municipal bylaws (Village of Grand Manan, 2015).

The Canada - New Brunswick Agreement (Canada-New Brunswick, 2005) required the Province to submit a public outcomes report every five years (Capital Management Engineering Limited, 2010). At the time of this research, only one report (2010) was publicly accessible on the provincial website. Email inquiries to the Province in August 2015, as a follow up to interviews conducted with provincial staff, to access the 2014 report indicated that the report was in the final stages of review and would be posted to the Government of New Brunswick website in the near future.

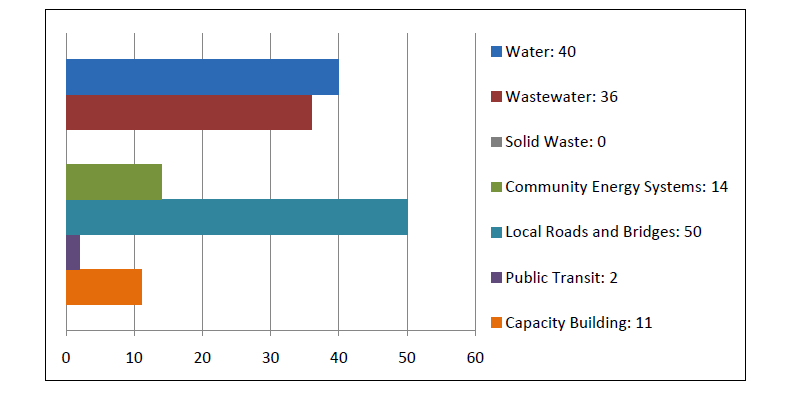

The 2009 report (Capital Management Engineering Limited, 2010) noted that the Gas Tax Funding Program (GTFP) in New Brunswick supported “construction, refurbishment, life extension and/or expansion of publicly owned infrastructure” (2010, p. 2). These infrastructure projects, summarized in Figure 1 referred to as Environmentally Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure (ESMI) were seen as essential for the delivery and administration of “potable water, wastewater collection and treatment, solid waste energy efficiency and clean energy local roads and bridges, and public transit” (p. 2). GTFP capacity building dollars were assigned to only local public service providers.

As a final point, without an updated provincial planning framework that revamps and potentially integrates the Municipalities Act, the Community Planning Act and the Regional Services Delivery Act transferring authority to local government institutions, the flexibility required to conduct and implement place-based sustainability planning will remain a challenge. This research suggests that the original intent of the Gas Tax Funding agreement was to provide the confidence of long-term resource and political commitments to municipalities, but that critical piece of provincial policy change has not yet occurred in New Brunswick.

The research further suggests that commitment must come from the provincial government in the form of legislative change and transference of authority back to the regional communities in order to reduce the mistrust and barriers to sustainable community development progress, due to lack of local decision-making authority and autonomy. This is supported by recent climate change research that has shown that the most innovative communities are those that have policy alignment within local municipal departments and policy congruence between levels of government (Dale A. , 2015).

As such, the Gas Tax Fund and the requirement for an ICSP could have been the impetus for real sustainability planning at the municipal level in New Brunswick. It is not too late. Now that the fund has become permanent, the province can choose to use those funds to encourage sustainable community planning and long-term implementation through the newly formed Regional Service Commissions that create a forum for municipal and non-municipal regional collaboration.

Finally, if the Province is to continue to distribute the GTFP funds based on a population criterion, then the Regional Service Commissions, similar to the County Councils (Province of New Brunswick, 2015) operating before authority was transferred to the Provincial Government, would seem a more efficient system. By providing dollars on a regional basis, funds currently controlled by the province for the unincorporated areas who are as one interviewee noted “living on the fringes of municipalities and utilizing services” their tax dollars do not fund, would be included. This too, supports the concept of flexibility noted as a result of this research as essential to supporting the creation of sustainable communities bounded by locally determined needs.

Figure 2: Distribution of Gas Tax Funding Projects by Category

Note: Adapted from New Brunswick Gas Tax Fund Outcomes Report, p. iii, by Capital Management Engineering Limited, 2010 (Capital Management Engineering Limited, 2010)

Additionally, the Province required that each municipality that received Gas Tax funding, file an annual report using a Performance Measurement Framework (PMF) template and indicators provided by the province that allows the Province to track results from all of the projects undertaken, summarized in Table 4 (Capital Management Engineering Limited, 2010, p. 17).

Table 4: Performance Measurement Framework Indicators

| Water | Length of water main repaired, replaced or added |

| Decrease in energy consumed | |

| Number of new connections to Municipal or regional water systems | |

| Waste Water | Number of new connections to a municipal or regional wastewater treatment system |

| Length of wastewater collection lines repaired, replaced or added | |

| Solid Waste | Decrease in energy consumed |

| Weight of material recycled or diverted from landfill | |

| Volume of methane captured | |

| Community Energy Systems | Number of power generation plants |

| Decrease in energy consumed | |

| Local Roads and Bridges (including Active Transportation) | Length of highway improved to meet Provincial standards |

| Length Travel distance reduced | |

| Length of improved or realigned highway that reduce travel time | |

| Increased trail or sidewalk use | |

| Public Transit> | Increased public transit ridership or capacity |

| Reduction in fuel consumption | |

| Number of reduced vehicle use |

These individual reports were not accessible, so content could not be reviewed for the purpose of this research.

In New Brunswick, a list of optional sustainable development indicators summarized in Table 5 suggests social, environmental and economic indicators that could be used to assess a “community’s level of sustainability” (Province of New Brunswick, n.d., p. 1) during planning and subsequent plan evaluation processes. The document advocates sustainability as having three key goals: “a healthy environment, a vibrant economy, and social well-being” (n.d., p. 1).

Table 5: Sustainable Community Indicators (Province of New Brunswick, n.d.)

| Environmental Indicators | Social Indicators | Economic Indicators |

|

|

|

Conclusions

The need for flexibility in sustainability planning processes is conclusively proven from the results of this data. All participants noted that the tools dictated by the province employed within antiquated legislation negates the flexibility required for unique communities and sustainability as an evolving process (Dale A. , 2001). Additionally, a minority of interviewees thought ICSPs, in and of themselves, might be “too prescriptive and too overwhelming for municipalities” to implement successfully. When engaging the community, interviewees found the particular objectives/actions/wants in an ICSP were too ‘specific’ and too much for the municipality to implement without the ability/authority to influence other actors (e.g. key stakeholders, and other departments).

The influence of staff and elected officials, based on their individual experience and education, to affect sustainability processes was highlighted by one participant as “sustainable development is something that higher level politicians have to understand and have to be versed on to be willing to in some cases overrule their staff”.

Moreover, a number of interviews emphasized this personalized role of staff in planning process including “when I came I recognized it was a necessity” and “it didn’t happen because I wasn’t here at that time.” This staff personalization of planning processes can be viewed as both a barrier and a driver for sustainability. A barrier in the context that implementing sustainability requires, as one interviewee noted, “partnerships and committees are needed to achieve those goals… it’s not just engineering and environmental, it’s all departments”.

However, even staff influence on planning processes was seen as constrained by the province due to legislation that dictates municipal planning limiting their capacity to expand on planning processes applicable to their local needs. Several interviewees supported this as a constraint of sustainability planning in New Brunswick, noted by one as being “extremely centrally controlled” and municipalities have to “do what has been legislated and told to us to do by Fredericton” leaving “very little wiggle room or freedom to basically do anything that is outside the provincial legislation”.

Contrastingly, one case study did find the GTFP to be flexible in its application, permitting its use to fund a development project in response to a social issue that was gaining negative national media attention. Although this too was noted as being due to the role of the individual provincial leadership and political influence at the time, not due to an effective distribution model. A distribution model currently based on population that “has no real validity for what needs are or where we are going” and typically “provides minimal funds to depressed areas” as noted by interviewees. Other than British Columbia, New Brunswick is the only other province that has chosen to employ this centralized system of GTFP distribution inhibiting the ability of municipalities to develop their own plans based on localized needs.

This recognition of localized needs in each municipality was evident in the cases of Saint John and Moncton that developed very different ICSPs even though they used the same consultant. This uniqueness was most likely due to the benefits of sustainability planning which recognizes the flexibility requirement for each municipality to develop a plan without a one size fits all planning approach.

Further supporting the need for flexibility in municipal planning processes is the fact that processes to evaluate locally plans were found to be unique for each case study community. These ranged from a simple internal annual review by Council to reporting from all municipal departments on the status of specific objectives.

Although the Province was given flexibility in the distribution of the Gas Tax Fund Program, in both the initial GTFP agreement and the new 10-year agreement going forward as summarized in Appendix 5, the province did not cede that same degree of flexibility to their municipalities. In fact, there are a number of changes, in the new administrative agreement with New Brunswick (Government of Canada, 2014) highlighted in Appendix 5, that emphasize the provincial jurisdiction over municipalities going forward versus the language in the original agreement suggesting collaboration with all levels of government in the original agreement.

This further exemplifies the New Brunswick government’s hierarchal control of municipal processes preventing flexibility to govern at the level closest to the people. This is further reinforced in the new agreement that incorporated “regional delivery mechanisms” (Government of Canada, 2014) in place of an inclusive broader community delivery language supported by Dale (2001). Furthermore, both the current and original agreements recognize the need for investment in smaller jurisdictions; however, the new agreement now incorporates a population criterion (Government of Canada, 2014) suggesting sufficient investment in smaller jurisdictions will not occur.

Overall, this research found that the Gas Tax Funding Program (GTFP) played a minimal role in the advancement of sustainability in New Brunswick due to the inflexible provincial planning and implementation models. Integrated Community Sustainability Plans, or the incorporation of sustainability in municipal plans, was found to be conducted for one of two reasons: 1) it was anticipated to be a future legislated requirement or 2) to access funds. In the case of the latter related to the GTFP, municipalities anticipated that even though it was not a requirement in New Brunswick initially, it would become so in the future in order to access the program. All interviewees seemed to recognize the value of sustainability in their planning processes, describing it in all cases, similar to the Brundtland Commission definition but interestingly with an emphasis on tangible developments (i.e., infrastructure). This was evident in interviewee statements that included the suggestion that sustainable development “was tied into the other pillar of infrastructure and infrastructure need” within their planning process and a community member who described sustainable development as “bringing the greatest benefit to the community from any initiative…a government sponsored infrastructure project”.

Interviewees noted that the provincial government does seem to recognize the value of sustainability plans and that community involvement is key, suggesting that is why the earlier regional sustainability plans developed by the Commissions were not used, as they “really did not include community”. Although all plans submitted to the Province by municipalities are used by government staff to “ensure the municipalities are requesting funds to support the priorities listed in their plans” this too can be viewed as another level of control negating any flexibility in implementation by a municipality for their unique context (Dale A. , 2001). One interviewee noted that “stronger more viable communities do sustainability planning” while also emphasizing communities are not encouraged to spend money on something they do not have the capacity to sustain.

The need for flexibility in sustainability processes is an imperative reinforced as a result of this research. All participants noted that tools dictated by the Province employed within antiquated legislation negates the flexibility required, recognizing each community is unique and that sustainability is an evolving process (Dale A. , 2001). Additionally, some interviewees noted that communities that did develop Integrated Community Sustainability Plans (ICSP) thought they may be “too prescriptive and too overwhelming for municipalities” to implement successfully.

This prescriptive approach to planning seen in those that did submit an ICSP, suggested there is an influential role of the individual in sustainability processes as noted by Dale (2001). This was noted in all cases, whether an ICSP was completed or not. The influence of staff and elected officials, based on their individual experience and education, to affect sustainability processes was highlighted by one participant as “sustainable development is something that higher level politicians have to understand and have to be versed on to be willing to in some cases overrule their staff”.

Moreover, a number of interviews emphasized this personalized role of staff in planning process including “when I came I recognized it was a necessity” and “it didn’t happen because I wasn’t here at that time.” This staff personalization of planning processes can be viewed as both a barrier and a driver for sustainability. A barrier in the context that implementing sustainability requires, as one interviewee noted, “partnerships and committees are needed to achieve those goals… it’s not just engineering and environmental, it’s all departments”. On the other hand, every individual can be viewed as a driver for change, engaging elected individuals in a position to effect legislative change to understand the benefits of sustainability planning.

However, even staff influence on planning processes was seen as constrained by the province due to legislation that dictates municipal planning limiting their capacity to expand on planning processes to make them applicable to their local needs. Several interviewees supported this as a constraint of sustainability in New Brunswick, noted by one as being “extremely centrally controlled” and municipalities have to “do what has been legislated and told to us to do by Fredericton” leaving “very little wiggle room or freedom to basically do anything that is outside the provincial legislation”.

Although legislation was viewed as a barrier to municipal sustainability planning, there was generally support for the new asset management planning requirement to access the GTFP funds as “infrastructure in New Brunswick is old and in need of repair”, as noted by one interviewee. But, information also suggested that the gas tax funding distribution with only an infrastructure focus does not lead to sustainability, emphasized by one interviewee stating that “it is not pipes in the ground, it is quality of life for people” which requires “flexibility to use it for non-infrastructure needs.”

Contrastingly, one case study did find the GTFP to be flexible in its application, permitting its use to fund a development project in response to a social issue that was gaining negative national media attention. Although this too was noted as being due to the role of the individual provincial leadership and political influence at the time, not due to an effective distribution model. A distribution model currently based on population that “has no real validity for what needs are or where we are going” and typically “provides minimal funds to depressed areas” as noted by interviewees. Other than British Columbia, New Brunswick is the only other province that has chosen to employ this centralized system of GTFP distribution inhibiting the ability of municipalities to develop their own plans based on localized needs.

This recognition of localized needs in each municipality was evident in the cases of Saint John and Moncton that developed very different ICSPs even though they used the same consultant. This uniqueness was most likely due to the benefits of sustainability planning which recognizes the flexibility requirement for each municipality to develop a plan without a one size fits all planning approach.

Further supporting the need for flexibility in municipal planning processes is the fact that processes to evaluate locally plans were found to be unique for each case study community. These ranged from a simple internal annual review by Council to reporting from all municipal departments on the status of specific objectives.

Although the Province was given flexibility in the distribution of the Gas Tax Fund Program, in both the initial GTFP agreement and the new 10-year agreement going forward as summarized in Appendix 5, the province did not cede that same degree of flexibility to their municipalities. In fact, there are a number of changes, in the new administrative agreement with New Brunswick (Government of Canada, 2014) highlighted in Appendix 5, that emphasize the provincial jurisdiction over municipalities going forward versus the language in the original agreement suggesting collaboration with all levels of government in the original agreement.

This further exemplifies the New Brunswick government’s hierarchal control of municipal processes preventing flexibility to govern at the level closest to the people. This is further reinforced in the new agreement that incorporated “regional delivery mechanisms” (Government of Canada, 2014) in place of an inclusive broader community delivery language supported by Dale (2001). Furthermore, both the current and original agreements recognize the need for investment in smaller jurisdictions; however, the new agreement now incorporates a population criterion (Government of Canada, 2014) suggesting sufficient investment in smaller jurisdictions will not occur.

Overall, this research found that the Gas Tax Funding Program (GTFP) played a minimal role in the advancement of sustainability in New Brunswick due to the inflexible provincial implementation model. Integrated Community Sustainability Plans, or the incorporation of sustainability in municipal plans, was found to be conducted for one of two reasons: 1) it was anticipated to be a future legislated requirement or 2) to access funds. In the case of the latter related to the GTFP, municipalities anticipated that even though it was not a requirement in New Brunswick initially, it would become so in the future in order to access the program. All interviewees seemed to recognize the value of sustainability in their planning processes, describing it in all cases, similar to the Brundtland Commission definition but interestingly with an emphasis on tangible developments (i.e., infrastructure). This was evident in interviewee statements that included the suggestion that sustainable development “was tied into the other pillar of infrastructure and infrastructure need” within their planning process and a community member who described sustainable development as “bringing the greatest benefit to the community from any initiative…a government sponsored infrastructure project”.

Interviewees noted that the provincial government does seem to recognize the value of sustainability plans and that community involvement is key, suggesting that is why the earlier regional sustainability plans developed by the Commissions were not used, as they “really did not include community”. Although all plans submitted to the Province by municipalities are used by government staff to “ensure the municipalities are requesting funds to support the priorities listed in their plans” this too can be viewed as another level of control negating any flexibility in implementation by a municipality for their unique context (Dale A. , 2001). One interviewee noted that “stronger more viable communities do sustainability planning” while also emphasizing communities are not encouraged to spend money on something they do not have the capacity to sustain.

Policy Recommendations

Executing policy, such as sustainability planning, is best undertaken at a level of government where it is not only effective but “closest to the citizens affected and thus most responsive to their needs, to local distinctiveness, and to population diversity” (Canada Ltée (Spraytech, Société d'arrosage) v Hudson (Town), 2001), also known as the subsidiarity principle (Dale, Herbert, Newell, & Foon, 2012). There is a decentralization trend in federal and provincial legislation and case law, reflecting an increasing stature of municipalities and the role they play (Lidstone, D., 2004). However, a corresponding transfer of resources has not accompanied this devolution.

In New Brunswick, this decentralization trend is evident with the creation of the Regional Service Commissions (RSCs) (Province of New Brunswick, 2015). The RSCs have created an opportunity to increase the capacity of municipal governments to collaboratively plan and take advantage of resource sharing opportunities on a regional basis, bringing incorporated and unincorporated areas to the same table to develop a regional strategic plan and to make decisions collectively. To date, provincial policies have not been updated allowing for the transfer of real authority to the Commissions (and subsequently local governments) for planning and resource management decisions or the administration of local resources (i.e., capacity building, planning) required to implement planning processes.

This may be related in part to the current political structure in New Brunswick that continues to sponsor a semi–quasi decentralization of power to local authorities, as in the case of the Commissions. As such, local control as the next step in local governance reform has not occurred, even though government commissioned reports over the past two decades recommend increased regional planning, sanctioning greater authority for local managers, most recently the Report of the Commissioner on the Future of Local Governance (Finn, 2008).

Although provincial planning systems remain focused on economic development without an embedded vision of sustainability that encompass social, cultural and environmental services, each case study, in spite of very little flexibility in their planning processes, has instinctively, incorporated some sustainability in their planning. As in the case of St. Andrews and Grand Manan, where these processes may not be a formal ICSP, template or toolkits would advocate suggesting a more applicable solution would be a flexible sustainability planning policy supported by the province with development and integration processes that allow local ownership and management. Perhaps one solution would be the application of Principles of the Commons (On the Commons, 2015) that advocates the collective management of resources within a defined community with a focus on equitable access, use and sustainability.

Instead of this collective and collaborative approach, the current provincial planning policies have created several layers of overlapping and controlling bureaucracy that mitigates against the advancement of sustainability at the local level. Municipalities in the Province have retained their Planning Advisory Committees (PAC) as per legislation (R.S.N.B, 2015), while the Commissions, as required by the Regional Services Delivery Act (R.S.N.B., 2012) “provide land use planning services to all Local Service Districts” (Southwest New Brunswick Service Commission, 2015), the unincorporated areas. Thus, they have established a Planning Review and Advisory Committee (PRAC) (2015). Creating an additional planning layer, the Southwest Regional Service Commission, in the case of St. Andrews and Grand Manan, has created a Planning Management Committee (PMC), comprised of municipal CAOs, volunteer citizens, Commission staff and Board members. The PMC objective is “to provide advice and guidance” to the RSC Board of Directors related to “high level operational and strategic directions for Community Planning” (pers. comm., RSC staff, 2015).

This fragmented planning system and lack of transference by the province of planning and equitable decision-making authority has created barriers to sustainability planning and the implementation of ICSPs. This was also evident in the time spent observing case study actors in varied settings, which served to reinforce the fragmentation of planning systems, both development and implementation. Elected officials of municipalities mandated to plan within one piece of legislation and appointed (sometimes self-appointed)[sic] representatives of unincorporated areas operating with no legislative authority under another piece of legislation, are expected to operate under yet a third piece of legislation causing confusion and preventing progress towards any form of collective or co-ordinated planning. This observed fragmentation is a result of the dated legislation and the reluctance of the Province to transfer authority to the local governments. As a result, barriers are created for local actors working within antiquated planning systems to collaborate, in spite of the fact that the data reveals a unanimous understanding of the need to implement sustainable community development and the need to integrate it into local plans.

One could view the Regional Service Commissions’ objectives as supporting sustainability planning. Their planning mandate, currently focused on waste management and land use planning, could be considered the initial objectives for social, environmental and economic integration in longer term planning activities. Unfortunately, without the authority to adjust tax rates or to conduct regional planning the commissions are not able to promote sustainability (Telegraph Journal , 2015). Additionally, under the current system, the Commissions are unable to respond and conduct planning at the local level in response to adjusting community service needs such as declining waste management needs due to reduced consumer waste in recent years (pers. comm. PMC, 2015).

The Regional Service Commissions (2015) mandate reflects this support of sustainability, which states:

The Regional Service Commissions will be responsible for the development of a Regional Plan, the aim of which would be to better coordinate and manage development and land use within each of the 12 regions. More specifically, the Regional Plans will focus on strategies that foster sustainable development practices, that encourage coordinated development between communities, that influence and guide the location of significant infrastructure (e.g., major roadways, facilities, trails), and that enhance coordination of commercial / industrial development. Regional Plans will also serve as an important tool in better managing, protecting and harmonizing urban and rural landscapes and resources. (Southwest New Brunswick Service Commission, 2015).

In contrast, this research shows that small communities, with somewhat geographically predefined boundaries, as in the case of the Village of Grand Manan, had more flexibility to engage, collaborate and act based on the local socio-economic and environmental needs. This was further evidenced in the Town of St. Andrews with over 400 inputs in their planning process versus less than 100 in the both the City of Moncton and the City of Saint John. This suggests, that smaller communities are more engaged in their community planning processes and are able to influence their plans through an active community engagement process independent of using consultants. Both Moncton and Saint John used consultants to develop both their plans and the engagement process; St. Andrews used consultants to conduct background research, but not to create their plan and Gran Manan led their own plan development. Perhaps the continually shifting support for sustainable development planning stems from the persistent challenge of working across several government silos necessary to implement sustainability plans. ICSPs and respective policies would require cross-departmental and jurisdictional collaboration to be implemented effectively. Without this involvement and cooperation of several departments and agencies, plans could not be implemented (Finn, 2008, p. 124).

Since sustainability planning and implementation at local scales remains a challenge, a more appropriate rationale of planning that recognizes the individuality of each community, and flexible boundaries to support service demands (Feiock & Scholz, 2010, p. 145) is required. This is supported by the principles for managing the commons defined by Elinor Ostrom (2015) summarized in Table 6 , that could be applied to allow for more flexible local sustainability and ICSP planning processes.

In applying these principles, rules could then be developed that are unique and suitable for the social, environmental and economic needs of each community.

Table 6: Eight Principles for Managing the Commons

| 1 | Define clear group boundaries |

| 2 | Match rules governing use of common goods to local needs and conditions |

| 3 | Ensure that those affected by the rules can participate in modifying the rules |

| 4 | Make sure the rule-making rights of community members are respected by outside authorities |

| 5 | Develop a system, carried out by community members, for monitoring members’ behavior |

| 6 | Use graduated sanctions for rule violators |

| 7 | Provide accessible, low-cost means for dispute resolution |

| 8 | Build responsibility for governing the common resource in nested tiers from the lowest level up to the entire interconnected system |

Strategic Questions

- Does the use of outside expertise, that is, consultants influence the effectiveness of the community engagement process of an ICSP?

- Does the use of outside expertise effect the degree of implementation of an ICSP in the community?

- What should the balance be between community autonomy and provincial oversight, if any?

Strategic Questions

Baker, S., & Edwards, R. ("n.d"). Review Paper: How many qualitative interviews is enough? London: National Centre for Research Methods.

Bell, J. (2011). A position paper : Regional service delivery in new brunswick planning commission directors – A working solution. Fredericton: NB Planning Commission Directors.

Bohringera, C., & Jochemc, P. E. (2007). Measuring the immeasurable — A survey of sustainability indices. Ecological Economics, 63, 1-8.

Braun, R. (2007). Sustainability at the local level: Management tools and municipal tax incentive model. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 387-411.

Bricki, N. (2007). A guide to using qualitative research methodology. London: Medicins sans frontieres.

Brundtland Commission. (1987). Our common future. Geneva: United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development.

Canada Ltée (Spraytech, Société d'arrosage) v Hudson (Town), 114957 (Supreme Court of Canada 2001).

Canada-New Brunswick. (2005, 11 24). Agreement on the transfer of federal gas tax revenues under the new deal for cities and communities, schedule H – integrated community sustainability plans. Retrieved from Province of New Brunswick : http://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/lg-gl/pdf/GasTaxFund-Fon…

Canada-New Brunswick. (2015, 08 24). Gas tax fund. Retrieved from Environment and local government: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/lg-gl/pdf/GasTaxFund-Fon…

Capital Management Engineering Limited. (2010). New brunswick gas tax fund outcomes report. Fredericton: Government of New Brunswick.

Charlotte County Multicultural Association. (2015). Charlotte County Multicultural Association. Retrieved from http://www.ccmanb.com/

CHCO TV. (2015). CHCO TV; Independent community television. Retrieved from CHCO TV; Independent community television: http://www.chco.tv/programming.html

City of Moncton. (2015, 10 12). Immigrationmoncton.ca. Retrieved from Immigrationmoncton.ca: http://www.immigrationmoncton.ca/SplashPages/immigration-construction.h…

City of Moncton. (2015, 10 12). Income and earnings. Retrieved from City of Moncton: http://www.moncton.ca/Assets/Business+English/Income+and+Earnings-+City…

City of Moncton. (2015, 10 08). Moncton. Retrieved from Moncton: http://www.moncton.ca/Business/Moncton_Statistics.htm

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications.

Council of Ministers of Education-Canada. (2007). Report to UNECE and UNESCO on indicators of education for sustainable development: Report for Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Commission for UNESCO.

Dale, A. (2001). At the edge: Sustainable development in the 21st century. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Dale, A. (2015). Prioritizing policy. Protecting nature by ensuring that the law is for the land.

Dale, A., Dushenko, W., & Robinson, P. (2012). Urban sustainability: Reconnecting space and place. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Dale, A., Foon, R., & Herbert, Y. (2011, October 14). A policy agenda for Canadian municipalities. Retrieved 2014, from Community Research Connections, Sustainable Community Development: Retrieved from sites/default/files/u641/policy_agenda_for_canadian_municipalities.pdf

Dale, A., Herbert, Y., Newell, R., & Foon, R. (2012). Action agenda rethinking growth and prosperity. Victoria: Sustainability Solutions Group.

Denzin, N. (2009). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods, methodological perspectives. USA: Transaction Publishers.

Dillon Consulting Limited. (2008). Our saint john: Integrated community sustainability plan. Saint John: City of Saint John.

Dillon Consulting Limited. (2011). Shaping our future: The city of moncton sustainability plan (An integrated sustainability plan). Moncton: City of Moncton.

Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The academy of management review , 14 (4), 532-550.

Feiock, R., & Scholz, J. (. (2010). Self-organizing federalism: Collaborative mechanisms to mitigate intuitional collective action dilemmas. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Finn, J.-G. (2008). Report of the commissioner on the future of local governance. Fredericton: Province of New Brunswick.

Flick, U. (2007). Concepts of triangulation. In Managing quality in qualitative research (pp. 38-55). London: SAGE Publications, Ltd. Government of Canada. (2014). Infrastructure Canada. Retrieved from Administrative agreement on the federal gas tax fund: http://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/prog/agreements-ententes/gtf-fte/2014-n…

Government of Canada. (2013). Canada economic action plan; Jobs, growth and prosperity. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

Government of Canada. (2009, 04 03). Infrastructure Canada. Federal Gas Tax Funding to Double and Payments to be Accelerated . Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Government of Canada.

Government of Canada. (2014, April 1). Infrastructure Canada. Retrieved from Agreement on the federal gas tax fund: http://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/prog/agreements-ententes/gtf-fte/2014-n…

Government of Canada. (2013, 09). List of municipalities; New brunswick. Retrieved from Canada Revenue Agency: http://www.cra-arc.gc.ca/chrts-gvng/qlfd-dns/qd-lstngs/mncplts-nb-lst-e…

Government of Canada. (2009, 08 20). National summative evaluation of the gas tax fund and public transit fund. Retrieved from Infrastructure Canada: http://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/pd-dp/eval/nse-esn/nse-esn01-eng.html

Government of Canada. (2011). Statistics Canada. Retrieved from Census Profile: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/fogs-spg/Fact…

Government of Canada. (2011). Statistics Canada. Retrieved from Census Profile: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/prof/details/p…

Government of Canada. (2011). Statistics Canada. Retrieved from Census profile: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/prof/details/p…

Government of Canada. (2014, 10 21). The federal gas tax fund: Permanent and predictable funding for municipalities. Retrieved from Infrastructure Canada: http://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/plan/gtf-fte-eng.html

Hanson, T. (2014). Charlotte County Transportation Committee Ridership Survey Analysis. Fredericton: University of New Brunswick.

Intelligent Community Forum. (2015, 10 11). Intelligent Community Forum. Retrieved from Intelligent Community Forum: https://www.intelligentcommunity.org/

Jeb Brugmann. (1997). Is there a method in our measurement? The use of indicators in local sustainable development planning. Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 2 (1), 59-72.

Kates, R., Parris, T., & Leiserowitz, A. (2005). What is sustainable development? Goals, indicators, values, and practice. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 47 (3), 8-21.

KPMG. (2015). KPMG. Retrieved from KPMG: http://www.kpmg.com/Ca/en/about/Pages/AboutKPMG.aspx

Lauckner, H., Paterson , M., & Krupa, T. (2012). Using constructivist case study methodology to understand community development processes: Proposed methodological questions to guide the research process. The Qualitative Report, 1-22.

Law Society of New Brunswick. (2015). CANLII. Retrieved from Municipalities act, RSNB 1973, c M-22: http://www.canlii.org/en/nb/laws/stat/rsnb-1973-c-m-22/latest/rsnb-1973…

Lidstone, D. (2004). Assessment of the municipal acts of the provinces. Ottawa: Federation of Canadian Municipalities.

Lidstone, D. (2004). Assessment of the municipal acts of the provinces. Vancouver: Federation of Canadian Municipalities.

Ling, C., Hanna, K., & Dale, A. (2009). A template for integrated community sustainability planning. Environmental Management, 44, 228-242.

Moncton. (2015, 10 08). Moncton. Retrieved from Moncton: http://www.moncton.ca/page4.aspx

Muldoon, P., Lucas, A., Gibson, R., & Pickfield, P. (2009). An introduction to environmental law and policy in Canada. Toronto: Emond Montgomery.

New Brunswick Environmental Network. (2010). Green print: Towards a sustainable New Brunswick. Retrieved from New Brunswick Environmental Network: http://nben.ca/phocadownload/tools/Greenprint_2010.pdf

On the Commons. (2015, 10 08). Ostrom, E.; 8 principles for managing a commmons. Retrieved from On the Commons: http://www.onthecommons.org/magazine/elinor-ostroms-8-principles-managi…

Palys, T. (2008). Purposive sampling. The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods, 697-698.

pers. comm. PMC. (2015, 08 18). Planning Management Committee; meeting participation. St. Stephen, New Brunswick, Canada.

pers. comm., RSC staff. (2015, 09 08). Email communication. St. George, Pennfield, Canada.

pers.comm. (2015, 02 26). St. Andrews. (S. Farquharson, Interviewer)

Province of New Brunswick. (2008). Sustainable communities in a self-sufficient province: A case study for the greater Saint John region. Saint John: City of Saint John.

Province of New Brunswick. (2014). 2014-18 NB gas tax fund incorporated areas allocations. Retrieved from Government of New Brunswick: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/lg-gl/pdf/GasTaxFund-Fon…

Province of New Brunswick. (2011, 12). Action plan for a new local governance system. Retrieved from Environment and Local Government: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/elg/local_government/cont…

Province of New Brunswick. (2015, 09 03). Advice and recommendation to minister; Gas tax fund provincial capital investment plan - 2005 to 2019. Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada.

Province of New Brunswick. (n.d.). Be our future: New Brunswick’s population growth strategy. Fredericton: Government of New Brunswick.

Province of New Brunswick. (2015, 10 11). Community funding branch. Retrieved from Environment and Local Government: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/contacts/dept_renderer.139.1278.20105…

Province of New Brunswick. (2015, 02). Community profiles. Retrieved from Environment and local government: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/elg/local_government/cont…

Province of New Brunswick. (2015, 03 12). Community profiles. Retrieved from Environment and Local Government: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/elg/local_government/cont…

Province of New Brunswick. (2015). Community sustainability plans in New Brunswick. Retrieved from Environment and Local Government: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/elg/environment/content/c…

Province of New Brunswick. (2015). Community sustainability plans in New Brunswick. Retrieved from Environment and local government: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/env/pdf/SustainableCommu…

Province of New Brunswick. (2015, 08). Environment and Local Government. Retrieved from Gas tax fund: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/elg/local_government/cont…

Province of New Brunswick. (2015, 10 13). Five year capital investment plan for the GTF administrative agreement. Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada.

Province of New Brunswick. (2015, 08). Opportunities for improving local governance in New Brunswick. Retrieved from Government of New Brunswick: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/lg-gl/pdf/ImprovingLocal…

Province of New Brunswick. (2015, 10 11). Provincial and community planning branch. Retrieved from Environment and Local Government: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/contacts/dept_renderer.139.201851.201…

Province of New Brunswick. (2014). Provincial framework and principles; Creating sustainable communities in nb. CIP Conference. Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada: Government of New Brunswick.

Province of New Brunswick. (2015). Structure of the new regional service commissions. Retrieved from Environment and Local Government: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/elg/local_government/cont…

Province of New Brunswick. (2015, 04). Sustainable communities in New Brunswick. Retrieved from New Brunswick Department of Environment and Local Government: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/env/pdf/SustainableCommu…

Province of New Brunswick. (2015, 07 21). Sustainable communities; Toolkit for building sustainable communities. Retrieved from Province of New Brunswick: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/env/pdf/SustainableCommu…

Province of New Brunswick. (n.d.). Sustainable community indicators. Fredericton: Province of New Brunswick.

Province of New Brunswick. (2015, 10 11). Sustainable development & impact evaluation (branch). Retrieved from Environment and Local Government: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/contacts/dept_renderer.139.200999.201…

Province of New Brunswick. (2015, 10 1). Templates for the 2014-2018 capital investment plan. Retrieved from Environment and Local Government: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/elg/local_government/cont…

R.S.N.B. (2015). Municipalities act; M-22. Retrieved from Laws, Government of New Brunswick: http://laws.gnb.ca/en/ShowPdf/cs/M-22.pdf

R.S.N.B. (1973). Community planning act. Retrieved from Government of New Brunswick; C-12: http://laws.gnb.ca/en/ShowPdf/cs/C-12.pdf

R.S.N.B. (2012). Regional service delivery act; C- 37. Retrieved from Province of New Brunswick: http://laws.gnb.ca/en/Showpdf/cs/2012-c.37.pdf

Rametsteiner, E., Pulzl, H., Alkan-Olsson, J., & Frederiksen, P. &. (2011). Sustainability indicator development—Science or political negotiation? Ecological Indicators, 61-70.

Resource and Educational Consultants. (2009). An integrated community economic development plan for the town of St. Andrews, NB. St. Andrews: Resource and Educational Consultants.

Robinson, J. (2004). Squaring the circle? Some thoughts on the idea of sustainable development. Ecological Economics, 48, 369-384.

Rogers TV. (2015). Rogers TV. Retrieved from Rogers TV: http://www.rogerstv.com/page.aspx?lid=14&rid=496

Saint John. (2015, 10 09). Living. Retrieved from Saint John: http://www.saintjohn.ca/en/home/living/default.aspx

SC. (1867). Constitution Act, 1867. Ottawa, Canada. Retrieved from Justice Laws Website.

Silk Stevens Ltd. (2014, October). EIA registration: Wastewater treatment system for organics diversion Building Located at the solid waste transfer station; Grand manan island, NB. Retrieved from Government of New Brunswick: http://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/env/pdf/EIA-EIE/Registra…

Southwest New Brunswick Service Commission. (2015, 09). Regional planning. Retrieved from Southwest New Brunswick Service Commission: http://www.snbsc.ca/

Southwest New Brunswick Service Commission. (2015, 09). The planning review and adjustment committee. Retrieved from http://www.snbsc.ca/

St. Croix Estuary Project Inc ~ Eastern Charlotte Waterways Inc. (2014). Charlotte county community vulnerability assessment; Summary document. St. Stephen: St. Croix Estuary Project Inc ~ Eastern Charlotte Waterways Inc.