The Co-operators Group Limited: A co-operative business model

The Co-operators Group Limited: A co-operative business modelChris Strashok, Research Associate, Canada Research Chair in Sustainable Community Development, Royal Roads University

Ann Dale, Canada Research Chair in Sustainable Community Development, Professor, School of Environment and Sustainability, Faculty of Applied Social Sciences, Royal Roads University

Published January 7, 2011

Case Summary

The Co-operators Group Limited (CGL) is a Canadian owned and co-operatively run business and a national insurance and financial services provider. Through various products, it insures over 847,000 homes and 1.3 million vehicles, covers more than 41,000 farms and 120,000 businesses, protects over 665,000 lives, insures more than 267,000 employees, providess travel insurance to more than 965,000 Canadians and visitors to Canada, and provide creditor insurance to 1 million Canadians

(The Co-operators Annual Report, 2009). The co-operative business model is based on representative democracy and a model of co-operation, rather than competition. This ‘alternative’ model has allowed CGL to be competitive in the Canadian marketplace for over 60 years, while integrating sustainable development into its business lines, addressing the environmental, social and economic imperatives simultaneously.

Sustainable Development Characteristics

This case study demonstrates two key features of sustainable development—an alternative governance model, that is, a co-operative business model, and its attention to one of the most critical issues, climate change. The latter has created challenges for the insurance industry in responding to accelerating impacts. Environmental, human and economic costs associated with extreme weather events are increasing in frequency and severity year-over-year and, in 2009 alone, CGL saw these events generate 5,884 losses resulting in an estimated $55.8 million in claims.

The Co-operators has made climate change a priority by aligning its business practices with the Natural Step’s four sustainability principles and adopting the following goals to:

- mitigate the climate change risks to our business;

- pursue business opportunities related to climate change; and,

- use its business leverage to influence their stakeholders to reduce their emissions, manage climate change risks, and foster climate change solutions.

(The Co-operators Sustainability Report, 2009)

The biggest opportunity for CGL to change customer behaviour are the external products it offers to clients. By designing unique products such as its hybrid vehicle discounts, Enviroguard Coverage™, Socially Responsible Investments, Community Guard and Envirowise Discount™, CGL promotes more sustainable development choices to its customers.

The co-operative governance structure in and of itself has also been a key factor for embedding sustainable development principles into the organization’s operations. Operating as a co-operative means that the organization is guided by following seven co-operative principles:

- voluntary and open membership;

-

democratic member control;

- member economic participation;

- autonomy and independence;

- education, training, and information;

- co-operation among co-operatives; and,

- concern for community.

Thus, commitment to these principles ensures the company integrates both the social and economic imperatives of sustainable development with environmental concerns. As a group, CGL and its member owners have been able to create a network of support where knowledge and experiences around sustainable development can be shared and innovation can flourish. One board member put the intentions of CGL best, “we want to be a catalyst for change in our sphere of influence, be creative in developing sustainable underwriting and claims management and work towards anticipating the future to meet our member and client needs”.

Critical Success Factors

The success of CGL's model can be attributed to several factors: its deep commitment to the seven co-operative principles; strong leadership; its connection to community, and participation in and fostering networks of co-operatives. Since its inception, The Co-operators has been able to flourish due to committed leadership who had experience and a foundation in the co-operative model. From this experiential base, the organization has had the focus and forward thinking to invest in the development of its employees, fostering strong leadership within itself virtually uninterrupted throughout the entire life of the organization. CGL's commitment to co-operative principles ensures it integrates both economic and social concerns into the bottom line of its business, focusing on long-term business strategies and the value it provides its members beyond a purely economic return on investment. By working on behalf of its member owners, and not ambiguous shareholders, business decisions also take into account what effect they have on the communities in which CGL operates. This includes sometimes maintaining a presence in ‘non-profitable’ locations coupled with a commitment to tailor products for specific community needs. This collaboration ensures the company remains close to its grassroots. In addition to strong leadership, The Co-operators has benefited from the experience and support of the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool (prior to its demutalization) and farm-based prairie co-operatives, as well as stable access to economic capital (The Co-operators, n.d.(a)). The experience and guidance provided by these organizations was vital for CGL’s capacity to transition from the struggles of a start-up company to its current dominant place as one of the top insurance providers in the Canadian economy.

Community Contact Information

The Co-operators Group Limited

Guelph, Ontario, Canada

Email: the_cooperators_foundation@cooperators.ca

What Worked?

The Co-operators membership consists of forty-seven different organizations throughout 7 different regions across Canada. This diverse representation of businesses from across Canada ensures that a wide diversity of perspectives and critical on-the-ground information are incorporated into the governance of the company, creating a unique opportunity for direct feedback for continuous creativity and innovation. With a smaller member base, the challenges of member engagement are reduced and CGL has been able to create a closer and more intimate relationship with its owners. It also works hard on operating transparently while building trust within the community. The Co-operators takes this trust seriously and measures it externally. Monitoring this trust building has helped to keep the organization true to its original vision and purpose, and according to one interviewee, also being able to operate without fear of internal surprises or scandal is a refreshing way of doing business. This contributes to loyal employees and high retention rates, and value is placed on creating more than just a business connection but also a relationship with their employees. As one individual stated, they get to “live their personal values at work”. Finally, since the co-operative business model is based on serving the needs of the members now and in the long term, CGL is not constrained to providing only short-term financial returns on members’ investments. This focus on longer-term financial and social prosperity, combined with the democratic process used for making business decisions, results in decisions that members relate to and fully support, thus allowing the organization to move ahead quickly on creative and innovative initiatives once decisions have been made.

What Didn’t work?

Although founded and owned by strong co-operatives and co-operative associations, there is still not a strong co-operative network established within Canada helping to promote the co-operative brand or advantage. By their nature, co-operative models are not self-promotional; they are created in order to serve their member needs and are not an entity in and of itself, like a corporation. Therefore, co-operatives spend their time serving their members and not actively advertising their co-operative business model to the general population. This is compounded by the misconception within the general public regarding the significance and of the role co-operatives play and could play within Canada. The general picture of a co-operative is that of small, inefficient and often marginal business. When compared to corporations, many view the co-operative model as inferior and not as competitive in the marketplace. Democratic structures also tend to change slowly and have a hard time being nimble when making business decisions. However, by taking the time to make a well informed decision based on consensus and member input, more integral decisions are made with full commitment from all levels of the organization, allowing the organization to move quickly on the implementation of these decisions once taken. There may also be links to enhanced innovation, although more research needs to be conducted about this relationship. Finally, The Co-operators is a large company employing 5,102 staff members and 487 agents (The Co-operators Annual Report, 2009). As new employees are hired and as employees are located farther away from the head office, it becomes more difficult to ensure equal awareness and commitment to the co-operative values of the company. There is a continual need for management to expend time and energy on providing education to staff, to ensure they understand the foundational meaning of a co-operative business model, so that everyone works towards the same vision, goals and objectives.

Financial Costs and Funding Sources

Co-operatives are privately funded businesses, relying on a group of individuals (members) to pool their resources to raise sufficient operating capital. These individuals also need to be willing to receive a return on investment in a form that is not purely financial, realizing that they are investing in both themselves and their communities.

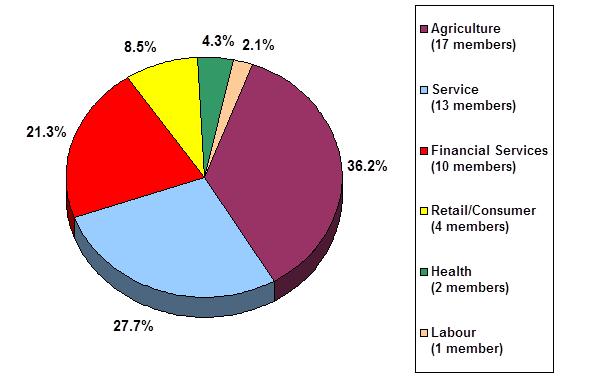

At its inception, in 1945, the initial funding for The Co-operators came from the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool, farm-based Prairie co-operatives, and the farmers that volunteered their time to sell the insurance (The Co-operators n.d.(a)) and, by 2009, their investors have diversified to include forty-seven organizations representing agricultural, services, financial services, retail/consumer, health and labour sectors, dispersed all across Canada. Their success in finding individuals supportive of the co-operative model is due to strong commitment to the co-operative principles, and this stable access to capital is one of the reasons for CGL's longevity. As a result, in 2009, CGL’s net income was $55.5 million and its annual total revenue was approximately $3 billion, while holding more than $36.9 billion in assets, making it one of the top three insurer providers in Canada.

As with all co-operatives, profits are either shared among member owners based on how much the member owner uses the co-operative or invested back into the co-operative to improve the services provided to the members, and sustain the business. In this way, the surplus profits remain local benefiting the communities in which The Co-operators operates. There needs to be a balance between providing a return on investment to the member owners and maintaining the financial viability of the business over the longer term.

Research Analysis

This research involved interviews with nine individuals associated with The Co-operators, using a semi-structured questionnaire, a literature review of journal articles relating to the co-operative model and documents from the company. Interviewees included a representative sample of front line employees, middle and senior managers, and board members. The interviews were open-ended conversations about The Co-operators itself, co-operative models in general, and the role they play in the Canadian economy and in the implementation of sustainable development.

Detailed Background Case Description

The Co-operators is a Canadian-owned and operated multi-product insurance and financial services provider started in 1945 when a group of Saskatchewan wheat farmers pooled their collective resources to start an insurance co-operative, providing life insurance for themselves and others in the community. By 1975, the Saskatchewan group joined together with a co-operative from Ontario, created by farmers looking to insure the transportation of their livestock, creating the foundation for the formation of The Co-operators Group Limited (CGL), in 1978 (The Co-operators, n.d.(b)).

The company has evolved into one of the top national insurance and financial services providers, which, in 2009, generated a net income of $55.5 million and an annual total revenue of approximately $3 billion, while holding more than $36.9 billion in assets. CGL employs 5,102 staff members and is supported by 487 agents in 651 retail outlets. Through its various insurance products, CGL insures over 847,000 homes and 1.3 million vehicles, covers more than 41,000 farms and 120,000 businesses, protects over 665,000 lives, insures more than 267,000 employees, provides travel insurance to more than 965,000 Canadians and visitors to Canada, and provides creditor insurance to 1.0 million Canadians (The Co-operators Annual Report, 2009).

The Cooperative Model

A co-operative is an organization that is owned by the members who use its services. All co-operatives must adhere to the seven co-operative principles:

- voluntary and open membership;

- democratic member control;

- member economic participation;

- autonomy and independence;

- education, training, and information;

- co-operation among co-operatives; and,

- concern for community.

The Co-operatives commitment to these seven core values has meant that the organization integrates both economic and social concerns into the bottom line of its business, focusing on a long-term business view and the value it provides to members beyond return on investment. Novkovic (2006) argues, however, that this integration of social responsibility into business practices is not unique to co-operatives and any investor-owned business can and does incorporate social responsibility and business ethics into their operations, calling into question the role these co-operative principles play in defining the unique co-operative advantage. Others argue that the degree of integration of social responsibility into traditional business entities is more shallow than deep (Dale, 2001; Dale, submitted; Roseland, 1999). This case study demonstrates that adherence to, and the open and transparent commitment to the principles of the co-operative model at the very inception of an organization make this unique to the co-operative model. Moreover, it also led to an early alignment and business leadership to more sustainable community development, defined as a process of reconciliation between the environmental, social and economic imperatives (Dale 2001; Robinson & Tinker 1997).

It is also clear that being a co-operative does not necessarily guarantee the application of the co-operative principles to business practices, without strong commitment and leadership around their implementation throughout a business. It does, however, make it more likely given the public declaration and commitment to these principles and their transparency, coupled with its governance structure. This is because co-operative principles are present right from the inception of the organization and form the foundation of the co-operative business model, placing the pursuit of economic goals secondary, to ensure that the aims of the co-operative are accomplished. This is in contrast to most investor-owned businesses where the primary focus is on maximizing profits with other goals and aspirations secondary and often flexible, allowing them to be reoriented to suit the needs of the investors and markets (Gertler, 2004).

All of the interviewees recognized the importance of the co-operative values and principles for The Co-operators. These values are the foundation of the business and are imperative to helping the business focus on why it is here now and in the long-term, while honouring the social contract the organization has with its membership. Embracing the co-operative values and principles has also ensured that CGL operates transparently, building trust within the community.

Governance Structure

Classified as a 3rd tier co-operative, CGL is the co-operative and the holding company owning 100% of the stock for The Co-operators group of companies. This organizational structure is a legal requirement as co-operatives are not allowed to sell insurance and means that the The Co-operators clients are not member owners like most traditional co-operative organizations.

CGL is owned by 47 member organizations reflecting the agricultural, service, financial services, retail/consumer, health and labour sectors (see Figure 1). Ten percent of its business is with member owners while the remaining ninety percent is with clients who may or may not be members. These member organizations appoint delegates, approximately one hundred and ten individuals, to act as their liaison with the company. Distributed throughout 7 different regions across Canada, these delegates review operations and provide input into the direction of the organization. They also form the pool of potential board members from which the regions elect twenty-two individuals to the board of directors for CGL.

Figure 1 – Membership by sector

Being a 3rd tier co-operative has meant having a relatively small membership base for an organization of this size. Because of this, The Co-operators has been able to relieve some of the tensions that are generally part of representative democracies (Cole, Herbert, McDowall & McDougall, 2010). It has the benefits of having a big enough membership to have diverse perspectives and ideas, while still being small enough to have a more intimate relationship with their members.

There are, however, unique challenges associated with representative democracy due to this governance structure. Since The Co-operators management does not nominate its board of directors, the board can potentially lack the required business skills and experience needed to govern the organization (Bond, Carter, & Sexton, 2009). This is a minor issue according to all of the interviewees, and CGL recognizes that an active democratic process requires time and energy, and an ongoing educational process. Therefore, as one strategy to deal with potential lack of skills, board education and engagement are key policies of the organization and new board members are not left working in a vacuum.

Also because of the diversity of perspectives and some sectors that are traditionally more conservative, decision-making through consensus means that the co-operative model, in general, can sometimes respond more slowly to business innovation. Once decisions are made, however, decisions are produced that members, who are both investors and consumers of the co-operative, relate to and fully support them allowing the organization to produce goods and services that are better received by the market and move ahead quickly on initiatives (Lotti, Mensing, & Valenti, 2006). The results of this democratic decision-making process often yields trust, greater commitment and the facilitation of shared knowledge (Birchall & Ketilson, 2009).

The trust generated between managers and members is essential to accommodate the flattened hierarchies in which The Co-operators and other co-operative models operate (Jones & Kalmi, 2008). Historically, this has not always been the case and The Co-operators has gone through some growing pains. Earlier boards were initially wary of the managerial level, as many of the managers did not have knowledge of the co-operative business model or did not necessarily share the same strong commitment to the co-operative's core values. Traditionally business management expertise had come from outside of the organization where co-operative values are not widely known nor understood, while the prevailing attitude of board directors was that managers were there only to do what the board directed. As Novkovic (2006) explains, this division between managers and members is common in co-operative organizations, and highlights the challenges to balancing the business and social functions of cooperative organizations in an environment where competitive corporations are the norm.

The board and internal staff relationship has subsequently evolved and become more nuanced over time as its members realized the important role managers play in running the day-to-day activities of the business. Equally, managers have come to understand more fully the co-operative business model and its competitive advantages. To further invest in this relationship, CGL has also started to develop leadership initiatives from within the organization, such as their Building Understanding and Influence for Leadership Development program (BUILD), to address the need for greater managerial competence (The Co-operators Sustainability Report, 2009).

Sustainable Development

CGL realized that before they were able to promote sustainable ways of doing business externally, it would need to get its own organization in order. In 2006, sustainable business practices were first discussed throughout the organization. Since then CGL has:

- engaged staff in paper reduction efforts, eliminating paper wherever possible and moving to environmentally sustainable products when paper is needed;

- reduced energy consumption by renovating and retrofitting buildings, updated electronic equipment, updated fleet fuel efficiency and reduced and eliminated unnecessary travel; and,

- adopted a sustainable purchasing policy for corporate and claims (The Co-operators Sustainability Report 2009).

With the understanding that if you do not measure it there is no point in doing it, each of these policies is outlined in The Co-operators 2009 Sustainability Report [report no longer available for download]. Each initiative is attached to specific goals providing a clear and accurate direction the business is taking. One interviewee noted that because this report contains vetted information that is reliable and accurate, staff at every level of the organization feel more informed and engaged, enabling them to become champions as well as senior management. This engagement encourages staff to look at their own individual sustainability actions and change their own behaviour while contributing to the overall goals of the organizations. An interviewee also noted the benefits of this self-reflection, stating that they probably would not have considered making these changes on their own accord.

Since the resources used and the waste generated by the insurance industry has a relatively small environmental footprint, the biggest opportunity for change is in the external products it offers to its clients. By designing unique products such as its hybrid vehicle discounts, Enviroguard Coverage™, Socially Responsible Investments, Community Guard and Envirowise Discount™ The Co-operators are promoting more sustainable lifestyle choices to their clients.

CGL has also taken their long-term view of doing business and applied it to developing the future generation of leaders within Canadian communities through the initiation of their IMPACT program. Started in 2009, the program is designed to empower youth and provide them with the tools and information they require to make a difference while also giving them an opportunity to create supportive networks amongst themselves. To provide ongoing support for these youth in their sustainable development projects, The Co-operators Foundation – Impact! Fund was created, which to date has provided a total of $83,685 to 13 students.

The Co-operators also reaches out, supports and mentors other co-operatives throughout Canada. In 2009, CGL supported the growth of seven co-operative organizations providing grants through their Co-operative Development Program (The Co-operators Sustainability Report, 2009). By creating strong relationships and perpetuating mutual cycles of reciprocation, a stronger co-operative sector evolves, opening up markets and connections to other networks for CGL and its members while building a stable and loyal customer base (Brown, 1997; Majee, 2008; Novkovic, 2006).

Role in Canadian Economy

As with any business in Canada, CGL’s role is to provide goods and services and jobs to the Canadian economy, and like any other business there needs to be a demand for these goods and services. In many instances, this demand is created by producing goods and services that are more convenient or better priced than what is currently available (Novkovic, 2006; Zeuli & Cropp, 2004). For CGL, this means being committed to providing stable and equitable financial coverage to all communities in Canada, even to areas, usually rural, that are deemed un-profitable by its competitors. This commitment comes from recognizing the complex value of communities and the need to serve these under-served individuals, therefore, fundamentally integrating the social imperative into their business bottom line. By being able to see past the initial outlays in the cost of operating in these communities, these opportunities are viable to The Co-operators, because the benefits go beyond a purely economic bottom line and contribute to the social mandate of the co-operative principles. This demand is also created by being flexible enough to design and customize products for different sectors within the Canadian economy such as their Community Guard offered to voluntary and non-profit organizations.

Co-operatives are also community based businesses, ranging in scale from a neighbourhood to a nation. Being a business operating at a national level means all of the profits generated by CGL stay within Canada and that Canadians are employed. This locally based business model also allows The Co-operators to be closer to the needs of the communities in which they operate giving them the ability to address market failures more quickly (Jones & Kalmi, 2008) and get resources into the communities that need and use them. This community engagement helps foster strong relationships between CGL, its members and its clients (Birchall & Ketilson, 2009; Herbert, Cole, Hardy, Lavallee-Picard, Fletcher, 2010; Lotti, Mensing, & Valenti, 2006).

Finally, because profits are shared with its members, The Co-operators has to be conscious of their overall growth strategies. This slower growth cycle combined with a longer-term view of business provides a balance to the drive for continual growth seen in our current economic paradigm. This slower growth cycle combined with a consensual decision-making process has allowed The Co-operators to sustain itself and avoid getting caught up in trends and bubbles that have often occurred in the overall global economy, since its inception.

Challenges of the Model

One challenge to the co-operative sector and to CGL in particular is a lack of co-operative brand. Since CGL was created as a tool to serve its member needs and is not an entity unto itself like a corporation, The Co-operators is not focused on marketing campaigns promoting the co-operative aspect of the company. Unfortunately Canada (with the exception of Quebec) also lacks a strong co-operative network, especially when compared to countries like Italy and Spain, to help promote the co-operative brand and advantage. As a result, there are many misconceptions about the co-operative model in Canada (Lotti, Mensing, & Valenti, 2006) and co-operatives are often assumed to be small- to medium-sized local affiliations that are not able to compete in the wider marketplace. This is ironic given that CGL is one of the top insurance companies in the country.

Two of the interviewees also revealed, and Christianson (2007) argues as well, that this lack of awareness is prevalent in all levels of Canadian government, and because of this, government does not actively promote co-operatives as a viable business model to the Canadian public, limiting the potential impact co-operatives could have on the Canadian economy. Due to this lack of knowledge, many of the policies and legislation pertaining to Canadian businesses, such as how capital is classified, the classification of dividends versus patronage payments and tax incentives for investing in co-operatives do not recognize the unique nature of co-operatives and limits CGL’s ability to be innovative with regards to financial arraignments with their members (Brown, 1997). In addition, the co-operative business model is also not taught in Canadian business schools further compounding this lack of awareness.

One way that The Co-operators is working to counter these perceptions and to educate individuals, and giving people the skills needed to operate co-operatives is through the funding the Master of Management: Co-operatives and Credit Unions degree at the Sobey School of Business at Saint Mary's University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. In addition, The Co-operators has also partnered with the University of Guelph to launch The Co-operators Center for Business and Social Entrepreneurship program

(The Co-operators Sustainability Report, 2009).

Another challenge faced by CGL is that of scale, that is, what is an optimal scale? It is a large company employing 5,102 staff members and 487 exclusive agents (The Co-operators Annual Report, 2009). As mentioned earlier, as new employees are hired and many are located farther away from head office, not everyone in the organizations is as aware of or shares the co-operative values as easily as those in head office. This can potentially move the organization away from the co-operative's original purpose, creating a real threat to organizational integrity. This is a question, however, not unique to the co-operative business model.

Overall, The Co-operators introduces an alternative business model to the current competition-driven model, while interacting with space, place and time in ways that compliments and brings balance to the corporate business model (Gertler, 2004). Connected and committed to the prosperity of the communities in which they operate, CGL accounts for the environmental, social and economic costs of its activities breaking down the silos between the profit and non-profit sectors (Dale, 2001; Levi & Davis, 2008) allowing its business to drive sustainable development initiatives, while producing quality goods and service.

Strategic Questions

- In what ways can The Co-operators help promote the co-operative business model within Canada?

- What government policies would be helpful for strengthening the co-operative sector in Canada?

- What makes the co-operative principles so important to the success of The Co-operators?

- Given that sustainability recognises ecological limits, what is the role of an organization like

The Co-operators in a no-growth economy? - How will The Co-operators balance rapidly increasing claims from climate-related damages with the co-operative principle of supporting communities?

- In what ways can The Co-operators help society create innovative solutions addressing the ecological, social and economic imperatives?

- How does this governance structure deter members from demutualizing The Co-operators, turning it into a private business?

- Do you see an instance where the company has not yet achieved full integration of sustainable development?

Resources and References

Birchall, J. & Ketilson, L. H. (2009). Responses to the global economic crisis: Resilience of the cooperative business model in times of crisis [Brochure]. International Labour Office, Sustainable Enterprise Programme. Geneva.

Bond, J.K., Carter, C. A. & Sexton, R.J. (2009). A study in cooperative failure: Lessons from the Rice Growers Association of California. Journal of Cooperatives, 23, 71-86.

Brown, L.H. (1997) Organizations for the 21st century? Co-operatives and “new” forms of organization. The Canadian Journal of Sociology, 22(1), 65-93.

Canadian Co-operatives Association. (n.d.). Co-op facts and figures. Retrieved December 12, 2010, from http://www.coopscanada.coop/en/about_co-operative/Co-op-Facts-and-Figures.

Christianson, R. (2007). Co-operative development in a competitive world. Retrieved July 21, 2010 from http://www.wind-works.org/coopwind/Co-operative%20Development%20in%20Competitive%20World%20Christianson.pdf

Cole, L., Herbert, Y., McDowall, W. & McDougall, C. (2010). Co-operatives as an antidote to economic growth. Sustainability Solutions Group.

The Co-operators Annual Report. (2009). We are evolving: The Co-operators Group 2009. Ontario, Canada.

The Co-operators Sustainability Report. (2009). Making an impact: The Co-operators 2009 sustainability report. Ontario, Canada.

The Co-operators. (n.d.(a)). 1940s. Ontario, Canada. Retrieved December 12, 2010, from http://www.cooperators.ca/static/pdf/en/History_1940s.pdf

The Co-operators (n.d.(b)). The Co-operators Group. Ontario, Canada. Retrieved December 12, 2010, from http://www.cooperators.ca/static/pdf/en/CooperatorsGroupEN.pdf.

Dale, A. (submitted). Introduction. In B. Duschencko, P. Robinson & A. Dale (Eds.), Urban sustainability: Reconciling place and space. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Dale, A. (2001). At the Edge: Sustainable Development in the 21st Century. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Gertler, M. E. (2004). Synergy and strategic advantage: Cooperatives and sustainable development. Journal of Cooperatives, 18, 32-46.

Herbert, Y., Cole, L., Hardy, K., Lavallee-Picard, V. & Fletcher, A. (2010). Literature review: Cooperatives and the green economy. Sustainability Solutions Group.

Jones, D. C. & Kalmi, P. (2008). Trust, inequality and the size of co-operative sector: Cross-country evidence. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 20(2), 165-195.

Levi, Y. & Davis, P. (2008). Cooperatives as the “enfants terribles” of economics: Some implications for the social economy. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 37, 2178-2188.

Lotti, R., Mensing, P. & Valenti, D. (2006). A Cooperative Solution. Strategy + Business, 43.

Majee, W. (2008) Cooperatives, the brewing pots for social capital! An exploration of social capital creation in a worker-owner homecare cooperative. Milwaukee, WI: University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Novkovic, S., 2006. Co-operative business: The role of co-operative principles and values. Journal of Co-operative Studies, 39 (1), 5–16.

Robinson, J. & Tinker J. (1997). Reconciling ecological, economic and social imperatives: a new conceptual framework. In T. Schrecker (Eds.), Surviving Globalism: Social and Environmental Dimensions. London: Macmillan.

Roseland, M. (1999). Natural Capital and Social Capital: Implications for Sustainable Community Development. In J. Pierce & A. Dale (Eds.), Communities, Development and Sustainability across Canada (pp190-207). Vancouver: UBC Press.

Zeuli, K. A. & Cropp, R. (2004). Principles and practices in the 21st century. Milwaukee, WI: University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.