Salmon River Watershed Management Plan

Salmon River Watershed Management PlanChris Ling and Nitya Harris

Published March 20, 2007

Case Summary

The Salmon River Watershed Management Partnership (SRWMP) started out as a vibrant and committed group of stakeholders with a desire to produce an effective management plan to protect and conserve one of the last few remaining watersheds in the Greater Vancouver Regional District that is still able to support productive fish stocks. The partnership process suffered from a lack of sustained vision and commitment by some of the major stakeholders, a lack of community engagement and a final product that lacked depth and on-the-ground implementation. This was the result of competing and contrasting agendas, a lack of cohesive vision agreed across the partnership, and eventually a lack of consensus that created a toothless plan with no focus or authority behind it. The root cause of these problems was the poor governance involved in the creation and management of the partnership. It had no decision-making framework, the agencies involved never gave it any authority, and the various stakeholders had a lack of trust in each other and in the involvement of citizens in the process. This lack of integration of citizen and government groups on the round table contributed to the poor engagement with the public during the decision-making process.

Sustainable development Characteristics

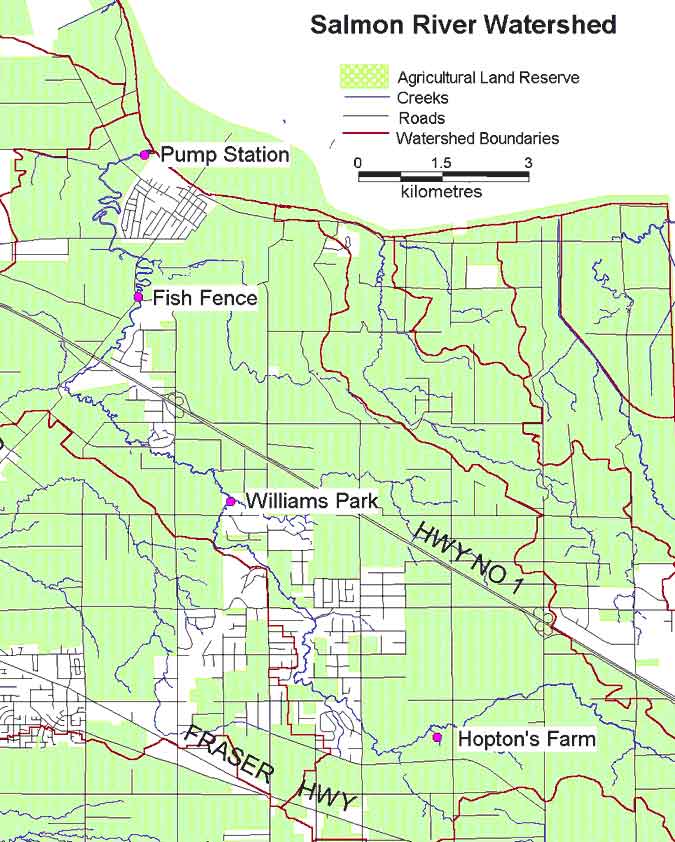

The Salmon River Watershed is considered one of the last few remaining watersheds in the Greater Vancouver Regional District that is still able to support productive fish stocks and although altered by development pressures, still provides good quality fish and wildlife habitat. It is also an area of fertile soils, attractive rural landscapes and underground water reserves. In 1993, the Environmental Co-ordinator of the Township of Langley noted that the protection of the natural resources in the Salmon River Watershed was seen as a priority for residents and users of the watershed. At the same time, a number of government agencies including the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) and the Fraser Basin Management Program were interested in having a demonstration project that showcased managing a watershed so that it was sustainable.

A number of issues exist that challenge the long-term health and sustainability of the Salmon River Watershed. Each individual issue by itself may not cause a large impact, but the cumulative effect of the issues could well be significant. Similarly, the partnership endeavoured to capitalize on the cumulative action of the various stakeholders in the watershed to move towards sustainability.

Many of the issues lead to conflicts between the agricultural community and development, between environmental and agricultural interests and between fishery and agricultural goals.

The major issues in the Salmon River watershed include the following:

Flood control: This issue pitches the interests of the agricultural community to control flooding for agricultural purposes versus the fishery and environmental interests to allow flooding to enhance habitat for fish and other species.

Agricultural Practices: The two major concerns regarding agricultural practices in the flood plain include the overloading of manure into the soil and the installation of dykes along the river.

Critical Success Factors

The early days were heady with enthusiasm and a drive to get things done. The leadership consisted of an energetic, intelligent group of people spearheaded by Peter Scales of the Township of Langley and the Langley Environmental Partners Society (LEPS) who acted as a bridge between municipal and civil society. The mandate and operating guidelines were unwritten, but known and accepted by the group – this worked well at the start when all members were committed to the process – it became more of a problem as the membership started to change.

The partnership aggressively investigated what the community wanted in the watershed. A fair amount of time was spent in exploring the concept of shared management and in identifying what the various stakeholders expected from the partnership. The stage was set for deliberative dialogue to occur on the key issues challenging the sustainability of the watershed.

A key advantage was the opportunity for the different agencies and stakeholders to pool their resources and then be able to allow the Langley Environmental Partners Society to implement much of the on-the-ground work through youth crews. The projects included data and map compilation, restoration of riparian areas, conducting stream surveys, livestock exclusion fencing projects, road signs at creek crossings, and storm drain markings.

What Worked?

The initial enthusiasm of the key people that brought the partnership together was crucial in starting and maintaining the process, and the leadership of Peter Scales, and his links between the township and the SWRMP (the deterioration of which caused his departure in 1997).

Early successes in the Salmon River watershed resulted from the setting the goals, and achieving them. This resulted in public interest as something was seen to be being done. As the relationship between the stakeholders deteriorated, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, public interest waned as more community linked members dropped out of the process and less tangible work was achieved.

What Didn't Work?

The community was invited to participate in the SRWMP at the start of the action plan development, but little participation was forthcoming. This may be due to the initial structure of the SRWMP not admitting members of the public, and a consequent gradual process of disillusionment with the institution over time.

As there was little documentation about the original vision and the mission of the partnership, an understanding of the rationale for the partnership was not shared amongst the people around the table. Strong personalities in the group and a continual disagreement with each other’s approaches led to the establishment of operating rules and conflict resolution mechanisms. The original process intended to have a series of committees and sub-committees form the action plan, however, whilst it was being developed a number of agencies were reducing their time commitments to the partnership so many of the sub-committees were disbanded. Consequently, most of the items in the Action Plan were worked out at the monthly meetings of the partnership with many proposals watered down for a consensus to be reached between all parties.

At the same time as LEPS and residents spent considerable time and money on restoration and prevention of destruction of habitat, a number of significant infractions in the streambed were allowed to incur without any consequences. Neither the DFO or the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks (MELP) took a strong stand on the enforcement of rules. Rather, they preferred to negotiate with the violators on a bilateral basis. The result was a corresponding disengagement, alienation and subsequent weakening of commitment to the process by the other stakeholders (Dale and Onyx, 2005).

This lack of enforcement spurred the creation of the Salmon River Enhancement Society, in 1995. Several founding members of the group who had been active in SRWMP found that there was a need for a separate citizens group, which could work with the government agencies, but would also increase public involvement and lobby the government agencies when appropriate.

After the first three years, a number of the key drivers of the partnership left and were replaced by others. At the same time, the funding that had initiated the partnership had run out and consequently, the coordinator’s position was terminated. Many of the replacements did not have an ongoing or shared vision for the group and momentum was faltering. In addition, some members of the SRWMP became disillusioned with the process. It became apparent that the management plan, when it was produced would, in reality, have little real impact on the management of Salmon River. This lack of implementation has proven to be the case.

By the middle of 2000, after innumerable revisions to the plan, SRWMP's members still could not agree and a push was made by a few members to finish the plan. By this time, the plan did not have many concrete outcomes, mainly recommendations, and was diluted to be acceptable to all the members. Furthermore, there was no commitment from the Township to implement the plan.

As members left the partnership, including the key founding members, the vision of the management plan faltered. This had a number of effects:

- The stakeholders lost interest and focus, resulting in a diluted plan that was too broad and too unfocused.

- The process was superseded by a fisheries/farmers conflict over the role of the floodplain. The fisheries wanted to maintain habitat integrity, the farmers wasted to construct flood defences. This led to the Town of Langley acting as mediator between federal and provincial agencies and the time and resources available to other elements of the plan were lost.

- As interest waned, the profile of the process within stakeholder organisations weakened, and people with less authority as decision makers attended meetings leading to a loss of integrity of the process.

Due to a lack of legislative oversight, the plan has no authority, perpetuating the legacy of weak enforcement in the area. This is partly due to a lack of interest in the plan by the community or the stakeholders in the partnership. The plan's lack of authority may also be attributed to it's broadness and lack of concrete commitments for the oversight organisations. The topics covered by the plan frequently cut across the responsible organisational boundaries. Without legislative authority, it is easy for the organisations to dispute responsibility.

Financial Costs and Funding Sources

The process was largely driven through the employment of a full-time coordinator. This funded position allowed for time and resources to maintain the profile and the momentum of the process. Once the coordinator position was discontinued, the process slowed and the partnership disintegrated. There was a brief resurgence when DFO assumed responsibility for coordination while the plan was being produced, but this role was also eventually withdrawn.

Research Analysis

Community partnerships can be a valuable and productive way of producing environmental management plans, enhancing social capital in the community in the process and bringing disparate groups together. However, it is difficult to maintain a partnership, or engage successfully with the wider community, if there is a perception that the resulting document will not have the impact or the policy/management relevance required to achieve the goals of the community or the stakeholders.

Such partnerships also have a momentum; once key people star to leave, or the process gets disrupted or slows down then that momentum is lost and the results are likely less than expected or required, leading to further disillusionment.

Setting out an initial consensus around a vision, or series of goals and building a plan around these shared values will ensure that the partnership works together from the start. The SRWMP did not have this shared vision at the start, and this led to a lack of focus to interest the public and intractable disagreements between stakeholders.

Detailed Background Case Description

The Salmon River Watershed Management Partnership (SRWMP) was initiated as a cooperative effort of federal and provincial government agencies, the Township of Langley and watershed residents. The partnership was established to move the management of the Salmon River Watershed towards sustainability.

The competing interests in the watershed are those of agriculture on an industrial scale, increasing urban development, a major golf course, and fisheries. The goal of sustainability necessitated a co-operative and accommodating means of interaction between these various interests while protecting the natural environment. As there was a lack of an entity that could plan across the watershed, the partnership was envisioned as the network that would take the lead in balancing the needs of all these stakeholders.

The partnership was originally set up as a government roundtable which consisted of a Steering Committee of Ministries and the Township. The broader vision of significant public involvement was not in place. A public committee of residents brought issues to the Steering Committee. The Langley Environmental Partners Society (LEPS) was also formed at this time to do the work on the ground and to source funding for the projects. Many of the residents attending the meetings were concerned about only one issue, and soon dropped out.

Through time, the government and citizen groups were integrated and the stakeholders now include various Ministries, the Township, environmental non-governmental associations, a farmers association, a golf course, associated academic institutions, and a few interested residents.

To promote awareness in the community, the members of the partnership wrote a series of articles in the local newspapers on a variety of watershed-related topics. And the open houses held by the artnership were well attended by the community.

In 1997, a Memorandum of Understanding was developed to document an understanding of all the members. Part of this process was the development of a vision and mission statement and the goals of the partnership. The members around the table also set out to draft a management plan for the watershed.

Two major projects were initiated and completed by the partnership at this time – the construction of a fish-friendly pump station and a public kiosk at Williams Park.

The constant renewal of the membership of the artnership resulted in a slow and arduous process for developing the management lan. Finally, in 1999 a co-ordinator was hired for the partnership with funding from the DFO, Environment Canada and in-kind contribution from the Township. The co-ordinator provided the much needed energy and commitment to complete the development of the management plan. The emphasis was placed on an action plan outlining the remedial actions and the associated responsibilities.

The partnership with the Township had also evolved at this time. Although the Township had been instrumental in initiating and leading the partnership in the early years, the political climate of the municipality had changed. A more business-oriented mayor and council came into place who did not share the same appreciation for environmental concerns. The partnership was largely ignored by the municipality.

The partnership saw the involvement of the Township as being crucial to implementing the management plan. With the Township’s interest waning over the value of the partnership, the management plan was soon put aside.

By the middle of 2000, after innumerable revisions to the plan, the partnership members still could not agree and a push was made by a few members to make the plan consumable to the majority. By this time, the plan did not have many directed items, mainly recommendations and was diluted enough to be accepted by all the members. Furthermore, there was no commitment from the Township to use the plan in any way.

The partnership was a good forum for discussion on various issues but was not conducive to decision making. A number of residents and environmental groups became frustrated at the lack of action. One key concern was the low standard of enforcement. As LEPS and residents spent considerable time and money on restoration and prevention of destruction of habitat, a number of significant infractions in the streambed incurred without any consequences. Neither the DFO or the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks (MELP) took a strong stand in the enforcement of rules. Rather, they preferred to negotiate with the violators.

A lack of interest characterizes the state of the partnership today. As one LEPS representative states “Working in partnership takes time, cooperation, sacrifice and understanding. I’m not sure that all the stakeholders are willing to continue putting in what it takes.” Limited resources preclude the hiring of a full-time co-ordinator and without a mandate, the group is rudderless. Most of the partnership stakeholders believe the process has ceased although there was never a formal dissolution.

As the partnership was winding up its management plan, the Township had begun its Water Resources Management Strategy to develop an integrated plan for the management of ground water and surface water for the entire municipality. Instead of using the partnership, another public advisory committee was formed and the partnership was given one seat on this committee. Although, several of the members of the partnership felt that SRWMP had been put aside by the Township, it allowed the partnership to participate in the Township’s process.

The focus of what was left of the partnership became largely directed towards flood management on the lowlands around the river – even the term floodplain became contested. Since 2002, this has been the chief concern of the remnants of the stakeholder partnership specifically the farming, fisheries and township stakeholders. The issue of flooding, flood control and its conflict with fisheries habitat formed one of the partnership’s sub-committees, but this sub-committee was the only meaningful group that survived the end of the management process.

This subcommittee contained some of the stakeholders of the original partnership, but far from all, and was dominated by the Town of Langley engineering department, and various federal, provincial and local fisheries and agriculture lobbies. The debate largely focused on the conflict between the desires of farmers to protect agricultural land, and the fisheries agencies that required the protection of habitat. The flood protection lobby was strengthened by perceived negative impacts of developments upstream and past bad land use decisions in the agricultural lowland areas putting pressure on the agricultural land. In addition downstream, in the City of Surrey flood defence systems have been built. Although the management plan did not allow for dykes, some landowners took is upon themselves to build them, with no legal teeth this was impossible to control.

More recently, the municipality has been embarking on a flood management strategy and the remnants of the partnership have been part of this process. The main stakeholders in this process have been federal and provincial agencies representing fisheries and farmers, with the Town of Langley acting as a mediator between them. The compromise reached is one of some areas of flood defence in the most valuable and at risk agricultural land, and some areas of natural floodplain and river habitat. It is not clear what the scientific rational of this plan is, or the support it has in the wider community. The Salmon River Enhancement Society and LEPS were not involved in this process.

Strategic Questions

- How does the lack of a collective vision or plan affect the long-term viability of community processes?

- Should there be a formal decision-making process be established between government and non-government stakeholders?

- Is there a relationship between the lack of a vision or plan and subsequent building of trust and social capital between stakeholders?

- What frameworks are required to ensure implementation in cases of multiple jurisdictions over management of a watershed?

- Is there a way to embed community processes such as round tables and community plans into the formal decision-making structures?

Salmon River Watershed Management Plan

This case study provided an excellent overview and critique of its successes and failures. The initiation of the SWRMP sounds very familiar to similar efforts and initiatives around the province. Documentation of the SWRMP process, challenges and struggles is extremely relevant and necessary for other projects being implemented, or underway. The people involved with the SWRMP, do share a vision, but sadly lacked cohesiveness and trust. When these two crucial elements are lacking or weak within an endeavor, dissolution is imminent. So rather than stakeholders focusing on their individual issues, perhaps an approach for future sustainable initiatives could also include coming to the table (all interested parties and stakeholders), laying all issues down – thereby having a better understanding of where each individual stakeholder is coming from (i.e. putting oneself in another’s shoes). This approach is often used during a process that is called Enowkinwixw (Okanagan word) that is an inclusion seeking process. When there is an issue or a problem, what is most needed is an understanding of voices that can’t be heard or cant’ be listened to (Armstrong).

Reference: Armstrong, J. Indigenous Knowledge and Gift Giving http://www.gift-economy.com/womenand/womenand_knowledge.html

Sustainability is a process not just an outcome.

This case study is interesting. I am the coordinator of a watershed group and we developed an integrated watershed management plan in 2012 in part to bring stakeholders together to collectively protect our freshwater resources but also as a guiding document for our long term goals and objectives. It can be located online at:

http://l.b5z.net/i/u/6058300/f/Integrated_Watershed_Management_Plan.pdf

Just speaking from my own experience, it seems that finding common visions and sustained commitments to watershed groups is a recurring theme that undermines the effectiveness of such groups. Government funding is another problem both if they get it and if they don’t. It is difficult to lobby against poor decision made by governments as it pertains to watersheds if your watershed group is funded by government. It is equally difficult to maintain an effective watershed organization if it does not receive consistent government funding. The constant turnover of key watershed management employees is a threat to a non-profit watershed group’s very existence and a drain on its energy and effectiveness.

I visited the Salmon River watershed groups web-site and noticed that this is still an active group with a great community macro-invertebrate monitoring program and annual updates to their web-site that detail the results of their data collection. I have read their watershed management plan and I think that it is a bit harsh to call it a “toothless plan with no focus or authority behind it”. Our provincial, municipal and federal governments have all kinds of regulations that are supposed to have authority and teeth, but also appear to be failing when it comes to environmental protection. Part of the problem with such groups is that unless there is a big issue or obvious threat to the watershed, it is difficult to get people to support a plan. People like to rally for a cause, and since the watershed macro-invertebrate sampling results are not indicating that current management strategies are hot causing any big problems in the watershed, there is little incentive to change the status quo.

Sustainable development is a process, not just an outcome (Dale, Dushenko, & Robinson, 2012). By going through the steps to develop a watershed management plan the stakeholders would have learned about the watershed issues at that time and even though they did not agree how to mitigate them, they learned about how the other stakeholders viewed them. It sounds like the stakeholders attended the meetings to argue for and defend their unsustainable use of the watershed resources instead of finding solutions to the identified problems. The apparent failure of this group appears to have more to do with social and economic issues than environmental ones.

When the municipality of decided to rely upon another organization to develop its water resource management strategy instead of the watershed management group and its existing partnerships, it likely undermined the credibility of the watershed group, which was unfortunate. However despite all of these setbacks, the watershed group did manage to accomplish some of its objectives and complete a number of projects designed to protect and conserve freshwater quality, and it is still active today so all was not lost. Hopefully, if the watershed group detects any change in the habitat quality through their monitoring program, they will be given the resources necessary to work with their stakeholders and fix it. This will be the true test of sustainability for the region. The watershed group has established the baselines through its monitoring programs so I would not be as harsh in my critique of this organization as this case study appears to be. How much can we really expect from an organization that was undermined by its stakeholders and struggles with inconsistent funding issues?

Dale, A., Dushenko, W. T., & Robinson, P. (2012). Urban Sustainability Reconnecting Space and Place. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Bumpy process of stakeholder partnerships

This case study unfortunately reflects some of the challenges of the participatory process. The diversity inherent in stakeholder partnerships lends itself to internal conflict (explicit or not), more so than any coalition of likeminded groups who share a common vision (Leach, Pelkey, & Sabatier, 2002).

In this case it appears the lack of groundwork done to develop a clear, common, and long term vision contributed to the disintegration of trust and cohesion amongst municipal, federal, and provincial agencies and the local environmental group. Furthermore, apparent lack of commitment of the part of federal and provincial agencies to enforce recognised environmental rules served to weaken stakeholder faith in the legitimacy of the process. Interesting to note the perceived paralysis of the SRWMP spurred the creation of a separate citizens group (Salmon River Enhancement Society) able to work with, lobby government agencies, and increase public involvement outside of the SRWMP process.

As for community engagement, after the initial excitement, the faltering support for the process was likely undermined by the late invitation for community input. By only inviting the community to participate at the start of the action plan and not admitting members of the public in the initial structuring of the SRWMP, it appears weak public trust in the process plagued the SRWMP from the outset. Despite the partnerships’ early efforts at community outreach, a lack of meaningful community input during the structuring process led to barriers to successful implementation and waning public engagement (Wagenet & Pfeffer, 2007).

As documented in this case study, the initial absence of a collective vision and decision making framework to guide the process seems to have led to subsequent stakeholder conflict, disillusionment, and disengagement. Hopefully lessons have been learned and the process is not prematurely abandoned because of failures at the early stages. Stakeholder partnerships as a collaborative policymaking process require time to overcome distrust, reach agreements, and begin implementation (Leach et al., 2002).

Leach, W. D., Pelkey, N. W., & Sabatier, P. A. (2002). Stakeholder partnerships as collaborative policymaking: Evaluation criteria applied to watershed management in California and Washington. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 21(4), 645-670.

Wagenet, L. P., & Pfeffer, M. J. (2007). Organizing Citizen Engagement for Democratic Environmental Planning. Society & Natural Resources, 20(9), 801-813. doi: 10.1080/08941920701216578

A cautionary tale

This is a tragic cautionary tale with few winners and many losers, including the Salmon River watershed itself.

Clearly the process would have benefiting from having a clear vision, and ideally an explicit commitment to working with a sustainability framework. If all the parties had agreed that they were there to reconcile the three sustainability imperatives (Dale, 2001), then they would have had a basis of unity, true social capital to build upon. From there they could work to identify, describe and quantify the driving forces for and against sustainability, and start to make trade-offs in a transparent manner. Those participants that were just there to stonewall would have been identified early on. Without this basis of unity participants would tend to default to lobbying for their own positions and interests rather than work together to realize a shared vision.

The lack of decision-making authority was another key weakness: without explicit commitment from the Township of Langley to implement the partnership’s decisions (as opposed to recommendations), there was little motivation on the part of those participants who benefit from the status quo to negotiate in good faith, and little reason for senior governments to take the partnership seriously. In fact, this process may have actually diverted valuable human and financial resources away from other approaches that might have had more impact, such as lobbying for changes to the Right to Farm Act (indeed, it appears the community realized this was happening which led them to create the Salmon River Enhancement Society). At worst, the existence of a process may have provided a “green screen” that became an excuse for some parties to avoid implementing needed changes. In this sense it can be argued that a weak and largely ignored plan, resulting from lowest-common-denominator decision-making, is worse than no plan at all.

The lack of decision-making authority in the process likely put unreasonable pressure on Peter Scales as the bridge-builder and leader. A better process with stronger buy-in from all parties would have not only motivated other champions to help Scales lead, but also would likely not have dragged on as long as it did, no doubt burning out participants along the way and thereby further decreasing social capital. A successful process on a shorter timeline may have achieved completion before the election of an unfriendly mayor and council; in fact, it may have even influenced the election!

I wonder what happened to the Fraser Basin Management Program? They are mentioned early in the case study, and never again. Why did they not intervene to put the process on track? Why did they not rescue their own demonstration project? I also wonder at the lack of First Nations involvement. Both the Kwantlen and Katzie Nations are listed as “partners” on the LEPS website, but they are not noted as being involved in the SRWMP.

One potential approach would have been to first hold some exploratory stakeholder conversations to float the idea of using a sustainability framework. If there was reasonable buy-in to that, a community-wide Future Search would be a good next step, allowing for a broad cross-section of perspectives to be heard and action plans to be developed. I am quite fascinated by this process tool, which claims that “[m]ore action and follow-up have come from a few days of Future Search than from dozens of smaller meetings over months or years” and which lists several case studies from US county, state and federal agencies, as well as hundreds of organizations, businesses, congregations, schools and universities that have used Future Search.

References

Dale, A. (2001). At the Edge: Sustainable Development in the 21st Century. Vancouver: UBC Press.

www.futuresearch.net