Transportation

TransportationCase studies in sustainable transportation infrastructure.

Alternative Road Allocations, Whitehorse

Alternative Road Allocations, WhitehorseLevi Waldron

Published January 24, 2007

Case Summary

This case study examines the practice of converting existing four-lane roadways to multimodal two-lane roads, often referred to as alternative road allocations or "road diets," although this study avoids the latter rather value-laden terminology. The road space gained from the reduction in automobile lanes may be allocated to bike lanes, widened sidewalks, a treed centre median, or other uses. The common feature is the reallocation of existing automobile space. The loss of automobile space is usually made politically feasible by improvements in traffic flow efficiency, for example adding left-turn lanes, harmonizing automobile speeds, and eliminating lane changes, which maintain preexisting car traffic flow rates. This case study focuses on two alternative road allocations, Fourth Avenue and Quartz Avenue, in Whitehorse, YK.

Sustainable Development Characteristics

Alternative road allocations hold the potential to enhance transportation safety for all road users, reduce congestion and transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions, encourage healthy active transportation, and improve aesthetic appeal of the roadway. The City of Whitehorse lists the following goals for its transportation infrastructure and education plan:

- reduction of transportation related greenhouse gas emissions;

- increased awareness and use of walking and cycling, particularly for downtown commuters;

- increased awareness and use of public transit and carpooling;

- improved safety for road users;

- greater use of cycling by city employees for business trips in the downtown area;

- greater public understanding of the linkage between transportation choices and greenhouse gas emissions;

- a healthier lifestyle for residents and visitors; and,

- reduced fuel consumption and congestion.

Critical Success Factors

Changing the status quo of existing road design priorities is a difficult and significant political risk. Acceptance by a sufficient majority of road users is critical both to implementing changes and keeping them in place, as evidenced by the rapid reversal of some of the redesigns in Whitehorse. In other cases, the redesigns have gained broad acceptance by ensuring that automobile travel times and volumes are unaffected or improved by the modifications. Alternative road allocations are not a technological "fix" to unsustainable transportation patterns; whether they remain in place and whether they provide an environmental benefit depends on the depth of government and public support for the principles and realities of sustainable transportation. To achieve substantial transportation sustainability improvements, they must be just a part in an ongoing process of incremental changes in attitude, habits, demand management strategies, and increased access to public infrastructure transportation choices.

However, for individual alternative road allocation projects to be approved and remain in place, some of the critical success factors are:

- an existing critical mass of support and demand for change from pedestrians, cyclists, transit users, and local residents who benefit the most from improved safety and aesthetics;

- minimal adverse effect on travel times for car users; and,

- the amount of parking along the roadway is unchanged or increased.

Essentially, to be politically feasible the alternative road allocation must be seen as a "win-win" situation, where some benefits to sustainable transportation users are realized without any sacrifice by automobile users.

Community Contact Information

Mr. Wayne Tuck, P.Eng.

Manager, Engineering and Environmental Services

City of Whitehorse

Telephone: (867) 668-8306

Fax: (867) 668-8386

Email: Wayne.Tuck@city.whitehorse.yk.ca

What Worked?

The Whitehorse alternative road allocation projects are part of a city-wide integrated greenhouse gas reduction strategy including other infrastructure changes, public education and outreach, and transportation demand management (City of Whitehorse, Stage 2: Detailed Proposal).

What Didn’t Work?

Upon completion of the Whitehorse 4th Avenue project, drivers along one stretch of road began experiencing delays during the evening peak period. One of the most disappointing outcomes of the alternative road allocation projects was the reversal of many of the project's important features only one month after completion. As a result of negative public feedback from some affected drivers, parts of the 4th Avenue project reverted to their former road allocation, including eliminating the separate bike lane in favour of designated bike lanes with on-street painted bike logos, and reversion to a four-lane roadway. The city is planning to widen the roadway to include a dedicated cycling lane in 2007.

Although surveys of improved recreational trails have indicated a 35% increase usage (Progress update of Whitehorse project), monitoring use of the new road system has proven to be challenging. This is due in part to the high variation in the number of people using alternative transportation, significant seasonal changes and limited vehicle traffic monitoring capacity (i.e., Whitehorse is not able to determine the number of occupants per vehicle). Thus, there is not yet an indication of whether the restructured roads and other efforts have produced significant changes in transportation choices.

Financial Costs and Funding Sources

Financial information for the Whitehorse project is from The Whitehorse Driving Diet (2003) and include only the actual costs of developing the infrastructure as the city did not include public consultations and other political expenses in the project's budget. The 4th Avenue alternative road allocation project, covering slightly more than 1km of road, cost $530,500 and was shared by the City of Whitehorse ($30,367), Yukon Electric and Yukon Energy ($50,000), and the Transport Canada Urban Transportation Showcase Program ($176,833). The Copper and Quartz Road alternative road allocation project cost $63,000, shared by the City of Whitehorse ($42,000) and the Urban Transportation Showcase Program ($21,000). The Robert Service Way and 4th Avenue roundabout project cost $110,000, which was paid for by the City of Whitehorse ($73,333) and the Urban Transportation Showcase Program ($36,667). These funds were used for:

- re-painting existing four lane roadway to two lanes with a centre two-way left turn lane and bicycle lanes;

- retrofitting traffic signals to suit new road geometry;

- adding parallel parking bays where required;

- installing mid-block crosswalks with refuge islands where needed for major pedestrian crossing locations;

- upgrading street signs and pedestrian/cycling markings;

- removing existing curbs where necessary to expand intersection area;

- constructing new raised concrete curb centre island and approach splitter islands; and,

- landscaping of the roundabout islands and edges.

Research Analysis

The City of Whitehorse is using soft and hard measures to determine the number of people commuting by alternative means to the downtown core, as well as other benefits from the infrastructure changes. Techniques include vehicle counts using on-street tube counts, intersection loop counting systems, visual traffic counts, trail intercept surveys, trail counters and city-wide surveys (City of Whitehorse Showcase Description):

- measurement of walking, cycling and vehicular activity using combinations of visual observation and on-street tubes, intersection loop counting systems, trail counters and trail intercept surveys;

- transit ridership counts and on-board surveys;

- motor vehicle collision records;

- interview surveys with pedestrians and cyclists;

- travel surveys of area households and downtown employees;

- travel logs maintained by carpooling and Travel Smart participants; and,

- participation in special events.

It has been difficult for Whitehorse to assess changes in transportation choices, due in part to the high seasonal variation in the number of people using alternative transportation and to limited vehicle traffic monitoring capacity (i.e., Whitehorse is not able to determine the number of occupants per vehicle). While trail surveys have provided good data, they may not be the best measure for determining accurate modal splits as the majority of trail use is recreational rather than transportation-related. A more conclusive follow-up report is expected in June 2007.

Detailed Background Case Description

Whitehorse is a small capital city of 21,000 people, with a downtown business centre and an “upper area” stretching several kilometres outside of downtown where about 2/3 of the population lives. Fourth Avenue and Quartz Avenue are two primary arterial roads connecting the upper area to the downtown, which were converted from four automobile lanes to two automobile lanes plus a two-way centre left-turn lane and bike lanes in 2004. A roundabout was also installed along 4th Avenue to reduce motorized vehicle delay, slow the speed of traffic, and improve the safety of all road users. The roads are also in the process of being beautified by burying overhead power and telephone lines, and upgrading the street lighting.

These projects are part of a larger process the the city began in 2002 to promote sustainable and active transportation. The process began with a public design workshop with city representatives, NGOs, and private citizens, which identified alternative road allocation options including replacing automobile lanes with bike lanes and installation of roundabouts. With further public consultation, these were incorporated into a city-wide transportation policy known as the Active Transportation Programme (Wayne Tuck, Personal Communication). At this point, the city made a successful application to Transport Canada's Urban Transportation Showcase Program. This program provided some capital funding for the infrastructure projects in exchange for being a showcase program and providing reports on the success and lessons learned from the program. Whitehorse's Active Transportation Program is multi-faceted, including (City of Whitehorse, Stage 2: Detailed Proposal):

- infrastructure changes to reduce barriers to active transportation;

- public education and outreach to promote greenhouse gas emissions reduction and information; and,

- transportation demand management programs to reduce the level of drive-alone travel.

All of the infrastructure changes outlined in the first stage of this proposal have been implemented. Actual construction on two alternative road allocations occurred in 2004, after another public consultation process just before construction. Upon completion of the lane reduction, drivers experienced delays along the downtown stretch of 4th Avenue during the peak evening rush. These delays may have been considered minor in many large cities, but caused immediate concern among drivers unaccustomed to such delays (Wayne Tuck, Personal Communication). Concerned drivers requested an emergency meeting of city council to review the changes, at which the city decided to revert two blocks of 4th Avenue to 4 lanes, eliminating the bike lanes for about 200 metres, but leaving over 1km of 4th Avenue in its new configuration. As part of the decision, council planned to reinstate the bike lanes at a later time by widening the road to accommodate them in addition to the four motor vehicle lanes – a “win-win” situation. “Quite a few people” felt that council overreacted, and should have given people time to adjust to the new situation (Wayne Tuck, Personal Communication).

These projects are relatively recent, but the City of Whitehorse has completed an opinion survey of the opinions of residents, and has taken efforts to measure changes in transportation patterns as a result of the modifications. Preliminary assessment of the success of these projects in meeting their goals are detailed in the Urban Transportation Showcase Program (2006) and summarized below:

- increased awareness and use of walking and cycling, particularly for downtown commuters: citizens survey in early 2006 found that "77% of citizens report that walking and cycling to the downtown core is good/excellent compared to only 49% in a 2002 survey and 47% in a 2004 survey";

- greater public understanding of the linkage between transportation choices and greenhouse gas emissions: citizens survey in early 2006 found that 96% citizens know about GHG reduction programs, with 68% reporting the they have made changes to their transportation means as a way of reducing their personal GHG contributions;

- improved travel time for cyclists, minor improvement for drivers;

- reduction of transportation related greenhouse gas emissions - not determined;

- increased awareness and use of public transit and carpooling - not determined;

- improved safety for road users - not determined;

- greater use of cycling by City employees for business trips in the downtown area - not determined;

- a healthier lifestyle for residents and visitors - not determined; and,

- reduced fuel consumption and congestion - not determined.

The 2006 citizens survey shows that the road transformations have improved residents' opinions of the walking and cycling-friendliness of these arterial roads and affected immediate aesthetic and safety benefits. However, this and other alternative road allocation projects have been designed to have minimal or no inconvenience to drivers, and there is still a lack of evidence that this approach will have a significant impact on transportation choices.

Creating a friendly street structure for cyclists, pedestrians, and transit users is an important aspect of increasing access to more sustainable transportation choices. Alternative road allocations are one aspect of the process for existing automobile-centred roads, but such projects are likely to meet stiff opposition from existing road users and be politically unpalatable if they try to change habits too quickly or without a broader recognition of the need for sustainable transportation and an integrated sustainable transportation plan. These initiatives are unlikely to achieve sustainable transportation targets such as Whitehorse's goal of significant greenhouse gas emissions unless they:

- build on existing initiatives;

- are part of an integrated strategy linking land use planning and transportation;

- are implemented in areas which already have enough support from local residents and businesses to pass the initiatives through the public consultation processes;

- have sufficient public commitment to their implementation and goals; and,

- are backed by the political will to maintain the project in the face of some negative reaction after implementation, which is inevitable even after extensive public consultations, and benefits are measurable and clearly communicated to road users.

In many places, the main barriers to implementing alternative road allocations are likely to be political will and public support, rather than actual infrastructure costs or technical challenges.

Resources and References

Interview with Mr. Wayne Tuck, P.Eng., Manager, Engineering and Environmental Services. January 24, 2007.

Urban Transportation Showcase Program website, Whitehorse case. (http://www.tc.gc.ca/programs/environment/UTSP/whitehorse.htm). Retrieved December 20, 2006.

Useful links:

Progress update of Whitehorse project

Road Diets: Fixing the Big Roads

Transport Canada website, St. George Street Revitalization: "Road Diets" in Toronto.

(http://www.tc.gc.ca/programs/Environment/utsp/st.georgestreetrevitaliza…). Retrieved February 12, 2007.

Re: Alternative Road Allocations, Whitehorse

As the Alliance petitions the Governor and the General Assembly to join together to ensure that any and all revenue collected from highway users are invested wisely. One wonders what these TIGER Grants are going to be used for. The Department of Transportation has so far lined up TIGER Grants, or Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery grants, part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act for St. Paul, Minnesota, Dallas, and a project in South Carolina. Dallas is getting street cars – it's anticipated that this might be a prelude to light rail projects, which are darlings of people that want public transport, but not as good as it could be. (The trolley systems used to be amazing, until GM manipulated congress to let them buy them out – thanks lobbyists!) It's basically huge payday loans essentially to our own economy, but one wonders when we'll see payoff.

- Log in to post comments

Alternative Road Allocations project comment

This case study along with the other three case studies found within the Transportation section of the Case Studies in Sustainable Infrastructure link all speak to the need for public engagement in the form of acceptance of the project by residents, cooperation and partnerships between government, NGO’s and the public and specifically, as noted in this case study, “an existing critical mass of support and demand for change” is required.

Despite apparent support through extensive public consultation and despite the fact that this alternative road allocation project was designed to have minimal impact to drivers, the City Council decided to revert part of the road back to its original configuration upon drivers’ complaints of traffic delays following the implementation of this road reallocation initiative.

It would appear that in regards to aspiring to sustainable transportation infrastructure we are challenged with balancing the need for public support that demands the implementation of policies that only require incremental changes of behavior against criticism of policies that do not appear to be sufficiently influential in achieving sustainability targets or having a significant impact on transportation choices.

- Log in to post comments

By converting the four lane

By converting the four lane roadways into multimodal two lane roads, we are allowing more traffic conjunction. The sustainable development characteristics is really essential for better road safety and the goals put forward by transportation infrastructure and education plan is practical to achieve

- Log in to post comments

Integrated Transportation Strategies, Mont-Saint-Hilaire

Integrated Transportation Strategies, Mont-Saint-HilaireJim Hamilton

Published September 15, 2006

Case Summary

In 2002, the Town of Mont-Saint-Hilaire put in motion the development of a multi-functional suburb focused around a new heavy-rail commuter station providing service to downtown Montreal. (www.ville.mont-saint-hilaire.qc.ca and www.levillagedelagare.com) Called Village de la Gare, the village uses transit-oriented principles. popularized in Europe and the United States, to put in place high-density development that:

- provides 1,000 residential units within walking distance to the station to be built over ten years, of which 400 are already constructed;

- reduces the need for automotive transport in favour of walking and bicycle paths;

- creates a multi-functional district -residential, commercial and institutional-within close proximity of the commuter station;

- allocates approximately a 14 per cent of the overall site to green space, including retention of natural characteristics such as stands of trees and interesting vistas; and,

- provides easy “walk-to” station commuting to Montreal. All residential units are within 750 metres of the station.

Beginning in 2002, the development, which will be phased in over ten years requires modifications to the town plan of Mont-Saint-Hilaire especially with respect to the distribution of zoning density and location, and will feature “old fashioned” building designs to better blend with the older sectors of the town and the rural nature of the surrounding area. The new commuter station is an extension of an existing heavy-rail commuter line to the south of Montreal, and was put in as an integral part of the development.

Data to date suggest a significant drop in automotive usage (although a formal study has yet to be undertaken), and a 30 to 40 per cent increase in the value of condominiums located near the commuter station. Design of the development has single family houses near the periphery of the community with a gradual transition from high to low density moving from the commuter station to the already existing community.

Key to the development was a conscious effort to put together a win-win situation to support Mont-Saint-Hilaire as an environmentally sustainable and scenic community, to increase commuter traffic, and to provide reasonable returns to developers.

Sustainable Development Characteristics

Village de la Gare purposely integrates the development of high-density accommodation with transit-supportive urban design. In short, it directly tackles the suburban problem by creating a village centre around a commuting station, permitting people to enjoy both the advantages of sustainable small-town living with the career choices that connect with the larger Montreal metropolitan area. For those not commuting, the purposeful design of a multi-functional community base near the station (that fully integrates commercial and institutional services with nearby residential units) supports the development of a healthy local economy and a livable community.

Located on a rehabilitated former industrial site (sugar refinery) near the edge of Mont Hilaire, the development aims to promote the natural setting at the edge of the mountain, while reducing development pressure around the mountain. This would be accomplished through installing services close at hand within the village, thus encouraging people to walk or bicycle.

The site had some minor contamination, primarily an elevated PH level. The developer paid for the clean up of the site rather than seek available government funding for the work as it was believed that the time required to apply for and comply with government processes would have caused undue delays in constructions.

Critical Success Factors

Critical success factors include:

- the presence of an existing train service within easy commuting distance to Montreal (about 35 kilometers) that was extended to Mont-Saint-Hilaire;

- the quality of the design and location of the station necessary to promote the use of the commuter train service thus leading to concrete results;

- acceptance of the project by the residents within the town of Mont-Saint-Hilaire. Following consultations within the community, the town put in place zoning by-laws that define high densities near the commuter station and lower densities moving away from the station towards an adjoining river and the existing town;

- the need to create and adhere to a long–term plan, and not be distracted by parties wishing to deviate from the plan; and,

- the development of a detailed integrated long-term plan, as well as the development of and control of standards related to type of housing, architectural styles, and allowable construction materials in order to maintain the overall integrity of the development.

Leadership for the project came essentially from the community as a response to protect the overall ambiance of the existing community, as well as the associated World Heritage site. Once conditions for developing Village de la Gare were in place, private sector interests made corresponding investments.

Community Contact Information

Bernard Morel

Town of Mont-Saint-Hilaire, Quebec

1-450-467-2854

What Didn’t Work?

The initial plan focused on preserving naturalscapes, especially land along the river, places to walk and enjoy nature, etc. and neglected to incorporate playing fields such as baseball diamonds and soccer pitches. This has been rectified.

Financial Costs and Funding Sources

Once fully developed, the project will require investments in the neighbourhood of $150 million. Initial investments and responsibilities are shared as follows:

- by the Agence métropolitaine de transport, which constructed the station, the costs of which will defrayed through commuter revenues and general provincial transportation subsidies; and.

- by the private developer whose costs will be covered through sales and leases of the residential, institutional, and commercial units.

Research Analysis

Analysis of this case study leads to these key observations.

-

- The critical need for a champion given the complexities associated with atypical land development. In this case, development depended critically on the ongoing and long-term cooperation of the people of the Town of Mont-Saint-Hilaire, the town council, the town planning committee, several provincial government departments, a metropolitan transit authority, as well as private developers.

- Zoning density is critical in transit-oriented sustainable development. Put simply, at Village de la Gare, development has to occur within 750 metres of the commuter station, which demands zoning densities significantly higher than those typically experienced in Canadian municipalities.

- The project focused on transit-oriented development (TOD), which generally subscribes to most, if not all, principles of sustainable communities. For further discussion of TOD, please refer to the TDM Encyclopedia at http://www.vtpi.org/tdm/tdm45.htm. The municipality of Mont-Saint-Hilaire extended these concepts well towards sustainability, especially when one considers that the town plan was adjusted to take into account protection of the UNESCO site and the agricultural and historical nature of Mont-Saint-Hilaire.

- The project takes full advantage of an existing capital investment, namely the rail link to Montreal. Putting aside financial returns normally associated with commuter rail links, the project in itself would appear financial viable. Most investments are from the private sector, and are based on returns earned through sales and leases. Public sector investments on basic infrastructure would be covered through usual tax levies, either development or land taxes.

Detailed Background Case Description

The Initial Situation

With a population of 14,500, Mont-Saint-Hilaire (www.ville.mont-saint-hilaire.qc.ca) is located approximately 40 kilometres from downtown Montreal on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River, and in part has served as a “bedroom” community for the larger metropolitan area. The town plays another role, however, in that it possesses a wealth of natural features, as well as having a significant a significant agricultural presence. In addition, in 1978, the UNESCO designated the nearby mountain to the town as a World Biosphere Reserve because of its unique biological and geological features.

In terms of size, the overall Mont-Saint-Hilaire community covers 43 square kilometres with 100 km of urban roads, 30 km of rural roads, and 24 km of highways owned by the Quebec Ministère des Transports. The town has four bus routes (two of which pass by the railway station).

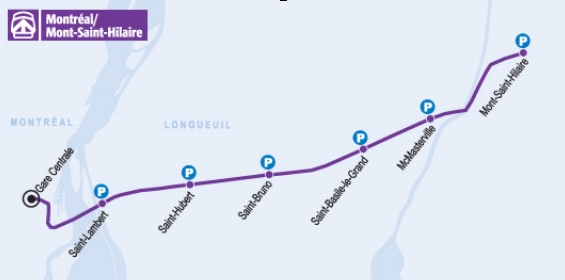

In 2000, the Agence métropolitaine de transport (AMT) (http://www.amt.qc.ca) restored rail commuter service to the south shore, and in 2002, as far as Mont-Saint-Hilaire. Departure and return times to Montreal are generally matched to conventional work schedules with four inbound departures to Montreal in the morning and four return trips in the evening.

Following AMT’s extension of rail service, the Town of Mont-Saint-Hilaire considered adopting a TOD approach to land development to create a sustainable community that emphasizes:

- high density;

- a within walking distance ‘city-centre’ that features a variety of functions, with residential, commercial, and institutional uses all close together in one area; and,

- conformity with the land surrounding the town, i.e. the physical features that led to the UNESCO designation, the agricultural community and the character of the older section of the town.

The Town of Mont-Saint-Hilaire is the first town in Quebec to use this concept, although it is very popular in Europe and the United States.

The Development Phase

Following the initial considerations, objectives were clarified in that land development had to:

- offer a new way of living in suburban Montreal, similar to what is being done in a number of the world’s major cities;

- create a multifunctional district or ‘city centre’ around the existing public transit system;

- preserve the town’s natural character;

- reduce development pressure around the nearby mountain; and,

- encourage a non-automotive environment.

This translated to a concept of developing 1,000 housing units on a completely rehabilitated former industrial site (sugar refinery) where the basic traffic area extended no more than 750 metres from the station, with land densities correspondingly higher in the immediate area of the station.

Four potential sites were studied, using multi-criteria analysis focusing on the functional and practical aspect of the station, traffic, user comfort, and infill development. The final choice was, to a large extent, determined by the physical location of the railroad bed, as well as the absence of contamination and minimal environmental impact.

Municipal Interaction

The project required extensive interactions on the part of the Town of Mont-Saint-Hilaire including:

- modifications to the town plan to incorporate sustainable development principles, especially the role of public transit to achieve this;

- harmonization of its by-laws and the issuance of construction permits in support of sustainability;

- re-zoning to establish the required distribution of building types and densities (high density near the station, low density near the river); and,

- inclusion within building permits of a site development and architectural integration plan that complies with applicable by-laws.

Technical Features

Technical features include:

- ultimate expansion to include upwards of 1,000 residential units;

- coverage of approximately 73 hectares (100 football fields), or 30% of the urban area of the town;

- development of the natural features such as a waterway and linear park;

- comprehension inclusion of traffic calming measures such as traffic circles, and a street grid design that makes it difficult for drivers to find short cuts to the station;

- a building layout that features older designs and conforms with the architectural style in the existing town,

- retention of tree stands;

- commuter station architecture reminiscent of traditional station designs;

- the use of berms to buffer train noise;

- the location of a 600-space “park-and-ride” lot is near the station; and

- railroad sidings located in the industrial area to reduce railroad noise.

Strategic Questions

-

What triggers a community to consider sustainability as a long-term objective?

-

Do the livability aspects of sustainability change dramatically across generations, and how important are these? Put differently, how important are economic incentives to community sustainability such as career and employment opportunities in line with those typical of a large metropolis?

-

What is the role of the private sector in developing long-term sustainability plans?

Resources and References

Cervero, R. 1998. The Transit Metropolis. Washington: Island Press.

Dittmar, H. & G. Ohland. 2004. The New Transit Town: Best Practices in Transit-oriented Development. Washington: Island Press.

TDM Encyclopedia “Transit Oriented Development" www.vtpi.org

The Town of Mont-Saint-Hilaire at www.ville.mont-saint-hilaire.qc.ca , and www.levillagedelagare.com

The Urban Transportation Showcase Program http://www.tc.gc.ca/programs/environment/UTSP/villagedelagare.htm

Heavy Rail Commuter Station

Nice case study. Very interesting.

What is a heavy rail commuter station. A regular non-commuter line converted for commuter use?

Where do these posts go?

Chris Severson-Baker

- Log in to post comments

Questions

Hello

This is an interesting case study as I know of St.Hilaire so am happy to see the initiative being taken in Quebec cities.

As discussed with Owen, I think that you are correct in your assumption Chris.

I am curious to know who or what started this initiative within the community as the study states that the leadership came from within the community. Their motivation must have been strong as they were not derailed in their quest for a sustainable transportation system.

I will have to see if I can find the ridership for the train and how successful it has been with linking the bus to the train station to increase ridership.

I am not sure where these posts go.

Sara

- Log in to post comments

Leadership

Nice pun - derailed.

I had the same question - it is left a myster in this write up - was this led my municipal government with community engagement? The write up suggests that private developers were not driving the process - engaging the community.

It is my sense that in Calgary - where I live - the municipal government convenes community engagement for changes to infrastructure (e.g. - widening a road) with the public when there is an established community - but i have not witnessed community engagement led by government in new areas. This tends to be done by developers - and the focus is on marketting the new development successfully rather than addressing concerns etc. I should pay closer attention to the process for infill development however...

Chris.

Chris Severson-Baker

- Log in to post comments

More questions

The write up mentions

a long range plan developed by the community was in place and was stuck to;

leadership came from the community;

the final impact of the development was 1000 residential unit and over 30% of the urban area;

the development was user pay (sales and receipts).

This is novel in light of your experiences in Calgary Chris and my own.

How do you get a collective vision? A long range plan? One so accepted it does not come apart at the first developer pressure?

Owen

- Log in to post comments

Transport or Walkability

This is an example of integrating transportation option to enhance the sustainability of the commuter town. What about trying to remove the need for transportation out of the town by increasing economic opportunities so people can live and work in the same place? How feasible do you think this is, and which should be the for community planners?

- Log in to post comments

Transport or Walkability

I suspect that in Montreal like other growing cities in Canada there is constant pressure on nearby communities as the new houses go to commuters. Sometimes the new community members are not able to afford a comparable house closer in to where they work - these people tend to be younger.

One approach that a community planner could take would be to look for ways to attract others on the demographic spectrum - like near retirees who will spend more time and money in the community which will create more employment in the community comared to one that is only being utilized during the day and weekends.

Chris.

Chris Severson-Baker

- Log in to post comments

I see two interrelated

I see two interrelated issues here: the sustainability of the community and the sustainability of the lifestyles of those who live in the community.

Removing the need for transportation would decrease the flows into and out of the community, potentially reducing the openess of the community. I would suspect the flux of money from the Montreal commuters into Mt. St. Hilaire has a tremendous impact both positive and negative.

Individual sustainability has to be considered for those who are commuting. Why do you live so far from your work? How long do you plan on commuting? What impact is this having on your family?

Owen

- Log in to post comments

Sustainability

Hi Owen

It looks like the commuter population is a part of the economic diversification of the town. I would imagine it may have been an agricultural centre at some point but that will have changed over time as things become more centralized.

AS for why people would like to live there. I know people who commute to Montreal from teh south shore for a number of reasons. A- they are from the area and work in Montreal, B- They don't want to live on the island in the city. C-They want to live in the country. D- they can't afford to live in teh city.

I am not sure how affordable these condos and houses will be and if they will be more so than on the island. However, if people want to raise their children in teh country this may be a much better option than in the city.

Cheers,

Sara

- Log in to post comments

Commuter: Individual sustainability

I am following you and thinking about individual sustainability, in particular the social aspect.

How sustainable is it to have one member of a family leave the community and commute to work on a daily basis? The commuter does not get to partake in the daily interactions of the family unit as he (or she) are gone before breakfast and return home after dinner.

I give as an example my daily commute which I do with my kids. I feel this is one of my most important interactions with them. When biking we discuss a variety of things from God, to their interactions with their friends. Most topics we cover are about a week old. The commute is a chance for reflection for them and my chance for input into their lives. I feel I am establishing a routine which I can use as they grow older (teenagers) and be able to connect with them.

It is half an hour I have each day with my girls. I also get to see their friends, their friends parents, and their teachers when I drop them off.

Owen

- Log in to post comments

Sustainability

With regards to Sara's point about people moving to Village de la Gare because they can't afford to live in the city, it states in the case study that the value of the condos in the area of the commuter station has increased by 30 - 40%. I am curious as to whether a price increase such as this creates barriers to certain segments of the population that the community may have been designed for/to attract in the first place, thus creating a homogenous community of high income dwellers.

GS

- Log in to post comments

I hear you Ginny Bowen

I hear you Ginny

Bowen Island just west of Vancouver (20 minute ferry ride) has possible an extreme version of this problem. The island has gone from a hippy hide out to an affluent commuter community. The cost of housing has increased so much that the services offered in the village are mostly staffed from Vancouver. You can't make enough serving in a restaurant to afford to live on the island.

I wonder if Mt. St. Hilaire has a social horsing policy in place as part of their Vision. Integrated - not segregated.

Owen

- Log in to post comments

Sustainable housing

Hi Owen

I have been thinking about the victorian type housing that you mentioned the other day and wondering if it really is sustainable? Would you not accomplish teh same thing in row housing? It may be more sustainable as if it was planned right, a large shared green space could be incorporated into the plans which would bring people together more so than the porches. It seems that the desire to have a single family dwelling is driving some interesting development. If the houses are so close that you can talk porch to porch then there is wasted space between teh houses as you can't really use it as it is so narrow. The other question is how often do people sit on their porches? The only people that I see sitting on their front porches are the the old people. Others tend to have back yard patios that they hang out on. If the green space was attached to the backyards of row houses than it would facilitate at least seeing ones neighbours and potential social interaction. I think that the desire to have a single family dwelling is not necessarily a sustainable thing especially with urban sprawl. I think that in cities we have to start getting comforatable with the idea of shared space and closer dwellings ie density. In rural areas things are different as people have been mentioning in class, although when housing starts taking over agricultural land then it is not a good situation, well in most cases I would say.

In any case, my two cents.

Sara

- Log in to post comments

Victoria style row housing

Sara points out Victoria style housing may not appeal to many people - on the other hand I have noticed that when backyards are connected people tend to build very large fences to block out their neighbours. The place where I live - has parking lots off to the side - and you have to walk in to get to your house and your house is attached to 4 other units. If you wanted to you could do a big circle walking through the complex for 10-15 minutes and never have to cross a road. But - most people hate the idea of not being able to drive to the front door.

Key to sustainability communities is alot of variety - so everyone gets what they want - but the community design does favor walking and transit over cars - and the density is appropriate for the area - and the buildings are smaller - and use dramatically less energy.

Variety is the key - with the house sizes

Chris Severson-Baker

- Log in to post comments

Transport or Walkability

As noted in the case study, integrating the development of high-density accommodation with transit-supportive urbn design tackle the "suburban problem" by creating a village centre around a community station, permitting people to enjoy the advantages of sustainable small town living with the career choices that connect with the larger metropolitan area.

Transit oriented development (TOD) has developed in response to the increasing trend toward commuter commnuties in an effort to minimize the reliance on vehicles therefore minimizing pollution and creating communities which favour person powered modes of transport within the community(e.g. walking and cycling) and provide residents with easy access to goods and services.

The development of transit oriented communities does create employment opportunities through the establishment of businesses required for delivering goods and services to the local community. However, the majority of employment opportunities that arise are likely to be low income opportunities (e.g. baristas, cashiers, salespeople etc.). If transit oriented development occurs in a community, I would suspect it would be difficult to create a context within which the career aspirations of those attracted to the commuter community could be met. Businesses that operate within cities adjacent to such communities operate within the downtown core for key reasons including proximity to their clientele, other business partners and suppliers. Relocation to a commuter town such as Mont St-Hillaire/Village de la Gare would thus not make sense for the majority of businesses operating within the city core.

My thoughts would be that the need for commuting could be minimized through the adoption of flex work policies by the businesses located within the city in recognition of the trend that their employees are not residents in the areas in which they work. Through such policies, people living in commuter towns may then be provided with the opportunity to work from home at least minimizing the number of trips required to and from the office in any given week. This also provides employees with the opportunity to get more out of their communities on the days which they work from home, and as Owen suggests in one of his posts to enhance the sustainability of their own lives through creating the space and time to interact with family and friends given time will not be used through a daily commute on those days.

GS

- Log in to post comments

Work options

Hi

Ginny, I agree that it is important to look at work options to see what can be arranged to cut down commuting. This can be done quite easily for some jobs but not so for others. I for one would be into working 1 day a week from home.

The other issue, is family and social dynamics. Yes, the commuting does take people out of hte village, but they are going to have to do that any way, it may be a choice or it may be their only option or the best option for their situation. Owen, I think that you are extremely lucky in your commuter option with your daughters as I do think that it is extremely rare and more challenging in different locations.

How can this apply to sustainable transportation. I think that we have to recognize that people are going to commute so how can we make that more sustainable. The other would be to start examining how to create situations which will increase someone's options so that they can choose more sustainable actions.

Sara

- Log in to post comments

Hi Sara, I wonder if there

Hi Sara,

I wonder if there is anyway that community can be formed on the commute? Back to the Bowen Island example. The layout of the ferry allows for large groups to gather and have discussions. The same boat every day has led to a community bulletin board to be established by the cafeteria so announcements and minutes from the community meetings are posted for all to see and read. I would look for some way for the commute to tie people to their Community.

My commute was extremely well planned. Part of my choice to locate to a smaller town was so I could be within bicycling distance of my work. All part of the choices we make. This one was made in consideration of my family and for personal health. Yes I am lucky to be able to make choices. The choice I made was not luck.

Owen

- Log in to post comments

What is a sustainable town?

Hi

Interesting point of whether or not the town should look at building up the economy so that people don't have to go into the city. We spoke about this idea during our discussion earlier today.

After our discussion, I was wondering what exactly is a sustainable community? Where are the boundaries drawn? I realize that there are the three social, environmental, and economic pillars, but when someone says a sustainable community what do you think of and what do you say it is? If a border is drawn around the community is a sustainable one one that can survive without having to cross over the boundary? Anyways.

The other question which is brought out with the otehr posts, are suburb or commuter communities (like st.Hilaire where people are commuting to Montreal for work) a one industry town such as a mining town or a forestry town (ie rely on only one economy as its major income source and once that is gone the community has a hard time surviving). Are there any other income sources. If the majority of hte money is coming in from the people working in Montreal (ie they make the money and use it to buy stuff in stores and it trickles down)instead of having other sources of income within the town, it does seem tor rely on one source. Although I suppose one could say that the people in Montreal work in different areas so it is not completely one source.

Although, if they have this park, there may be another source of income, tourism.

Cheers,

Sara

- Log in to post comments

Hi Sara In addressing your

Hi Sara

In addressing your first point on the sustainability of Mt. St. Hilaire from the three pillar approach. There is the UNESCO heritage site of Mt. St. Hilaire. I do believe that this is preserved due to its rarity of geological and ecological characteristics

I wonder what this does to give the community a sense of place and how this sense of place can be used to support the three pillars from an inside out approach. By this I mean instead of looking to Montreal for economic and social aspects can the community create them here?

The boundaries around the town will always have to be open. If tourism becomes an economic mainstay then people will have to come in.

Owen

- Log in to post comments

Boundaries and how do you know if a community is sustainable

Hi Folks

Yes, there will be some flux over the boundary but at what point do you say that is enough. About waste, does shipping your waste out of the boundary impact your being sustainable. I would say yes. At what point does one draw the line with all the interactions between areas with food and material goods adn cash flow?

Sara

- Log in to post comments

How to engage?

I agree with you sustainability requires an openness of boundaries and a flux of materials and energy across those boundaries. Similar to us as humans, food in waste out, ideas in ....stagnation or dynamic response.

How do you engage and understand and change in response to all the impact of those fluxes on the community, on the surroundings to the community, on other communities?

Owen

- Log in to post comments

Income sources

Hi

Just another quick thought. I was thinking along the lines of what you said Chris with trying to get retired people into the town. I would think that a situation like this may be quite apealing to an older person as it seems that there is a transition from single family dwellings to a condo with lower maintenance and work required. Being able to get around by walking may be another selling point as they don't have to drive and they do get their exercise, don't older people love to walk? I am not sure if they will need to get into town on a regular basis but it may be easier for them if they ahve to get into Montreal to get to a big hospital ie it may facilitate their mobility.

On the other hand, as only looking at the retired people coming into town, there will be money, I suppose it is another source ie not Montreal, but the focus will be on people support (Ie I can't remember the word but therapists and what not). SHould the town also be looking at attracting other industry or professional services (ie not heavy dute industry but creative things and engineering etc). So that money will be coming from multiple sectors.

Sara

- Log in to post comments

Motivation and context

Hello

I just had a thought tonight. I will have to reread the case study again and check it out. Initially when i read the case study my thought was what triggered the leadership within the community to develop this sustainable transportation system or little village with in their town. I think that I would like to know more about the motivation as I think that it will make a difference on the long term actions of the community.

I have thought about two possible reasons for the decision to go this way and I think that the long term outcomes will be quite different from the town for the two of them. ACtually the outcomes may not be that different just different time scales.

So the first thought is that they built levillage du gare based on a community need. It was a need within their community and they ran with it. Great. If this is the case, I believe that they should be able to move ahead with other areas of sustainable development within their community as they 'believe' in the concept or at least recognize its value and have enough motivation to do something.

The second motivation would have been a way to attract people to their town which was made possible as they had access to the railroad track and teh company was willing to work with them. THis may have been another economic sector and a way to keep the town alive and diversified. AS montreal grows, the towns around it are becoming more suburb like as people are communiting. However, I htink that ST.Hiliare is too far out to drive or only the die hards would do it. In order to get people to move to St.Hilaire would be to cater to the people looking to live outside of montreal and off the island. However, as the drive would be too long, by developing a train and sustainable communitication it makes it possible for people to live in st.hilaire and work in Montreal. If this is teh case, is sustainable transportation being used as a marketing ploy and not because the community really believes in sustinable development. If this is the case, I don't know how easy it would be to continue sustainable development within the town as it is not at their core yet, it is a marketing tool and current trend. However, over time if people are moving their as they are attracted to sustainable transportation, than as their numbers grow, they may be able to tip the balance and get teh town moving in a sustainable way in its other areas.

In the end does it matter what their motivation is? It was a good step forward but what will happen now and how will the town grow?

I would think that it would be important to know the context behind the councils decision so that if someone wants to continue sustainable development within the town they will be able to deal with the potential barriers and hurdle that they will need to get through to get the ball rolling. It will be easier to keep the ball rolling than to start it rolling.

Sara

- Log in to post comments

An observation

Mt. St. Hilaire is on the south shore of the St. Lawrence river. The south shore is generally less contaminated by urban sprawl most likely because crossing the river to Montreal must be a commuting nightmare due to the limited number of bridges.

The commuter rail capitalizes on its own segregated bridge.

Owen

- Log in to post comments

South Shore

Hi Folks

There is a actually quite a bit of sprawl on the South Shore. There are industries on the south shore as well as commuter towns. There are a few bridges and a tunnel in which you could access Montreal from the south shore. There are also towns such as Longueuil that has Pratt & WHitney Canada, there are also colleges etc. I think that there are more and more people moving to the shore as they want to get off the island. This commuter rail service should really help the commuter traffic.

Sara

- Log in to post comments

some points

Hello

After rereading the case study I had a couple of more thoughts.

So the town took advantage of the rebuilding of the railroad station to help add diversity to their town ie the Montreal commuters. It looks like the station is a small section of the town. The other thing which helped was that they didn't seem to have to put forth any funding ie the transporation agency paid for the railway station and the private developers paid for the buildings. The two things that I am curious about was who in the town actually planted the initial seed of sustainable transportation and if the town had had to pay for it, would it have been so successful?

To add to the successful integration of the community within the town and area there are probably a couple of things that they could do. In the area there is quite a bit of agriculture. I am just wondering if there are any farmers that would be interested in having a market of sorts at the station. It would benefit the community as it would be promoting locally grown produce and building social contacts within the community.

The second thought if they wanted to add to the economy would be to provide easier access to the UNESCO heritage site by having the train work on weekends in teh opposite way so that people in montreal who wouldn't be able to get to the park other wise, could take the train and explore the park. This would be good for the local economy for tourism and the local farmers could set up a market and it would be beneficial for the people in Montreal as they could get back to nature. There may also be a ski hill in the area so they could use the train to bring skiers from montreal to the hill as well.

Sara

- Log in to post comments

networks and nodes

Hi Folks

I was just think that we may want to explore some of the concepts that were discussed in class such as the context for this initiative, what is the shared value or meaning, what was the social structure that was used bonding, bridging and vertical, and the type of networks were needed to get this to work.

They needed a few different levels and government departments to get this off the ground as well as local buy in and the developers.

Within the community, what was done to get the people on side and how did they ensure that the long term plans were not changed. Was there a crisis? I don't know what the financial situation of the town is so not sure if they needed a greater tax payer base.

I was also wondering how the bus service to the train station is working and if they will develop a greater bus service for the town and local area to take advantage of the train station.

The developers also paid for the clean up, another thing that probably facilitated it for the town ie they didn't have to pay for it adn as the study says it was completed faster as they didn't have to wait for the government to do it. I am happy to see that the developers paid for it as they are the ones who will be benefitting finanically from this development and not the government (well directly I suppose). I am sure that they were able to cover the cost of clean up in the price of the houses and condos.

- Log in to post comments

Networks and Nodes - Limitations of Case Studies

Hi Sara,

I have also been thinking about the concepts in the course - and how they applied in the case study. It highlights a limitation of case studies - unless someone takes the time to write an entire book about what happened the case study is really just a teaser - it provides ideas but answers few questions.

I would be interested to know what was the percieved or real crisis that prompted the various parties to cooperate and fund studies etc?

I wonder too - how many of these creative sustainable community initiatives are as a result of a need vs reacting to a threat

Chris Severson-Baker

- Log in to post comments

segregated bridge

Interesting point - re: segragated bridge that may make the train more attractive than cars.

I think this is a key to enhancing public transportation in general - you can get there faster on the bus, train, etc even if it is not as comfortable. It was done by luck in this case - but it could be a policy choice to subsidize transit more than cars.

In car-first places like Calgary - it makes more sense to drive into the ocre some days because the bus takes just as long to get there - and you have to wait for it to come - and it drops you off close but not exactly where you want to go.

Chris Severson-Baker

- Log in to post comments

Heavy Rail Commuter Station

Chris

I do believe that heavy rail is a reference to using rolling stock and a rail bed similar to that used on industrial rail lines. It is more robust, expensive to build and as the name implies heavier so more energy to run. The Fraser Valley West Coast Express and the Toronto Area Go trains are examples of heavy rail commuter trains.

Light rail has little to no rail bed with lighter rolling stock. Vancouver's Sky train and Toronto's TCC Rocket are examples. They are great at stop and go between stations.

Owen

- Log in to post comments

Sustainable Community Development

Sustainable community development

One of the questions that arose in my mind when reading the case study was whether the development at Village de la Gare/Mont St. Hillaire satisfied the ecological, social and economic imperatives of sustainable development as we discussed in class. I wanted to provide a summary of my considerations in relation to this question.

Ecological Imperative

As was noted in the case study, the motivation for the development arose from the community in order to protect its overall ambiance as well as the adjacent heritage site. While TOD may satisfy these goals as defined by the community, it is unclear as to whether the development truly “works with nature”. As noted by Sara in one of her earlier posts, waste minimization and management was not clearly referenced in the case study. Given expansion of the community, what are the existing and planned efforts to minimize and manage waste? Given the surrounding area is largely agricultural based, is there potential to develop a community composting initiative in collaboration with farmers in the surrounding area? Such initiatives may serve not only to divert waste from landfill but also to minimize the requirement to transport waste. Further, the case study does not reference issues pertaining to water supply and discharge. Will locally available resources be able to supply sufficient water to meet the demands of the community? Where is the effluent from the community being discharged and can local waterways sustain such a discharge? While development of the community is focused around sustainable means of transportation for the commuter population, based on information in the case study, the development does not seem to truly satisfy the ecological imperative and work within the means of the local environment. It does not appear that the community has identified its context within the larger bioregion of which it is a part and whether the development will persist within the carrying capacity of the land to provide ecological services.

Social Imperative

Through review of the case study, it appears the majority of criteria for meeting the social imperative, including livability and quality of life, health and well-being, and community engagement, have been met. However, as was noted in our online discussion, the increase in the value of the condos surrounding the commuter station may not satisfy the equity and social justice criteria of the social imperative through creating barriers to lower income segments of the population.

Economic Imperative

The development of Village de la Gare was innovative insofar as they used concepts of TOD, a model popularized in Europe and the United States, in Canada. The development may provide the community with a competitive edge over other commuter communities in the area given access to the commuter rail station and the creation of a pedestrian friendly township with access to goods and services. The questions for me arise around whether the community will be able to provide its residents with a high quality of life at lower costs, and whether the development of the community will result in less resource use over time (e.g. the ability of the surrounding environment to meet water needs as well as assimilate wastes). The nature of the development also raises questions as to whether it will create conditions for economic resilience, diversity and adaptability. Further, I question whether the development of itself was designed and built in accordance with sustainability principles such as those set out in the LEED standard.

If sustainable community development is perceived of as a process of reconciliation which provides equitable access to resources (ecological, social and economic), it is not clear if Village de la Gare/Mont St. Hillaire could truly be considered a sustainable community, or one, in the words of Dr. Bell, that has truly connected the dots between the ecological, social and economic spheres which comprise sustainable development.

GS

- Log in to post comments

Waste in Quebec

Hi Folks

Just something to mention regarding waste and composting. THe government of Quebec has put in place some regulations about the various waste streams and managing waste. From what I understand there is a big drive (may be mandatory) for composting, recycling and to minimize waste to landfill.

Sara

- Log in to post comments

Community Participations

As per Chris’ discussion of Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation and South Lanarkshire Council’s Wheel of Participation in class, processes such as those implemented in the development of the Village de la Gare result in a degree of citizen power and empowerment through the effective participation of community members in the decision making and planning process. Both the local government and community members gained a better understanding of the issues the community considered important, resulting in an increased likelihood of support and success of the chosen development path. Processes to determine the path development was to take were also based on the knowledge of local community members. Community involvement in planning and decision making processes (which included development of a long term community plan) created a sense of ownership over both process and results, manifesting a stronger sense of belonging and place. Those that were actively involved in the process were also afforded the opportunity to enhance their skills and capacity as well as to develop new relationships and connections with others in the community, thus augmenting social capital within the community (Ling 2008, Griffiths 2001). The degree of community participation in the project likely had a strong influence over its success, emphasizing the importance of social capital in the implementation of sustainable development concepts at the community level.

GS

- Log in to post comments

Sustainable Development = Gentrification

One of the criticisms that is faced by sustainable development as a marketing concept, one that is very common in new green development, is that it is a value added commodity that prices folks out of the market - leaving them to suffer on the in sprawl development. This case is one example, Downtown Vancouver another example, Dockside Green here in Victoria another.

Is this just the inevitable way of the world, can sustainability be made available for all? What would happen if everywhere was developed in line with sustainable principles?

- Log in to post comments

Sustainability for all

Hi

Chris, you raise an interesting point about gentrification and the price of green development. Yes, I think that it is a marketing tool right now and people who can afford it are buying into it to ease their guilt. I thought that one of the things about Dockside Green was that it was suppose to provide for a community thus a certain percentage of its units were to be financially affordable to low income people. I believe that that was one of its mandates. However, I thought that I might have heard rumours that they were trying to work their way around this idea. The other question would be, what do they consider as low income. In any case, it does give a solution to gentrification which is through government ie permits, requirements to build, etc, low income green housing can be made available.

The other option is to get groups working together to make it affordable. In Ottawa, a cooperative managed to get a deal with: developers (they supply the solar hot water heaters at a whole salers rate (or something along those lines), a grant from NRCan, and the rebate that one gets for installing a solar hot water heater; which managed to get the cost of installing a solar hot water heater down to about $3000 from $6000. Now this is still too expensive for some but it does make it available to a lot more people at $3000 rather than $6000.

I suppose the other thing is that as long as it is not massed produced, the cost will be high which puts it out of the range of many people. But as there is more demand and more suppliers, teh cost should go down. It has over the past little while ie there are a lot more geothermal heat pumps going in now then there were a few years ago.

So what can be done? Is this something that hte government needs to take initiative with? In Ontario there are cash back schemes for making your house more energy efficient ie they give a certain amount back per window, door that is new. This is also at the Federal level.

The problem is the high front end cost. If there was a way that people could have access to funds at the beginning and pay it off as they realize the savings of the energy saving devices than it may be more feasible for people.

Sara

- Log in to post comments

What people are doing and what does technology permit

Hi Folks

It is late so I will try and be coherent.

It was brought up in class the other day that the size of houses has increased 3 fold (or a huge amount) over the past few decades. It has been facilitated by better building codes and material.

Just reflecting on my own situation and those around me, I don't have a lot of money so am very concious with heat, water, and electricity. I look around and see that others in a similar situation are consious of these factors as well. The reason for this (well I have other motivators as well) is the cost associated with these factors. If people don't have a lot of money they will try and cut costs by reducing their consumption. Therefore, they are being more "sustainable" then others who are not concerned about money.

With the houses, instead of saving resources overall, the resources going into houses increased (bigger houses) and the energy required stayed the same ie even though technology was better it didn't really save a lot, it permitted people to have the bigger houses at a similar operating costs. So they can say that their house is R2000 certified (or what ever standard) and that eliminates their guilt as they have done something for the environment.

I am wondering if it is the same for these other technologies. I suppose that they don't have quite the same environmental impact, however, does it take away the guilt and conciousness of people towards the environment ie I have green technology so I have done my part and keep going.

I am trying to remember which lecture, I think that it was Louise, who stated that basic solutions have been overemphasised so people think that they can continue their habits provided they recycle and buy energy efficient lightbulbs. In any case, does the green technology and how it has been marketed promote this type of guilt free behaviour or unresponsible behaviour. (I am trying to think of a better work for guilt).

In any case I would tend to think that people who are short of money do what they can to save money ie insulate their house, reduce consumption ie wear a sweater in the winter and light clothes in the summer.

Actually a completely other beef that I have is the business dress code. Part of the air conditioning demand is to ensure that men don't overheat in their suits. It seems a little bizarre to wear all that clothing in the summer. wouldn't it be better to be more casual so that the air conditionning can be turned down?

Sara

- Log in to post comments

Sustainable development = gentrification

Hi team,

As Sara noted, Chris L. raises an interesting concept in regards to green development pricing people out of the market. Another example of this is the Millenium Water (www.milleniumwater.com) development that is currently underway in Vancouver. A suite under 600 SF (not incl balcony) starts at $450,000 with the most luxurious of suites going for a cool $3.5 million. When I first heard about this new green development, I was very much interested in looking into purchasing a suite. However, as a first time home buyer, I was not prepared to sell my soul to the green devil to be able to truly live my values in this up and coming sustainable development complex. Millenium Water is not just pushing people in a low income bracket out of the market but those in the middle income bracket as well.

However, with that said, it is my hope (and we gotta have hope don't we?!) that as green building standards and sustainable community development practices become the norm instead of the exception, that the prices for living in green developments will come down.

Without relying on hope alone, there must be, as Sara suggests, pricing mechanisms through which developers can recover their ROI for installation of features that meet green standards/sustainabile development principles. For example, the development of innovative P3 partnerships may be one mechanism through which sustainable communities are able to become more accessible to all segments of the population.

GS

- Log in to post comments

An advanced town

Hi Folks

I was just looking through the environmental bulletin and cultural bulletin that the town has published and I think that they are a very dynamic town. It took a bit to find these publications, hence the late post. In looking at the dynamics of the town it makes sense that they were able to implement sustainable transportation. There is also an inter-municipality bus line that ends up in Montreal, so there was existing public transportation to Montreal for commuting, however I would imagine that the train is much more popular.

In any case, it seems that the town is very proud of its heritage and culture. The bulletin covered the art festival, the apple festival, the history, and published a long list of cultural activities that it will be putting on for the next 3 months (from the date of publication). They also promote the Biosphere Reserve (ie Mountain) as a unique area to be protected.

on the environmental side, they are moving ahead with waste reduction, GHG emissions, water use, pesticide ban, and community support. With waste reduction, they have to reduce the amount going to landfill by 60%, I think that they are aiming to have only 40% of their waste go to landfill by 2010. THis is a provincial initiative or at least there is pressure from the province. To do this they are only having waste pick up once every two weeks (following the example set by other communities in Quebec) which the mayor is really supporting. They have green yard waste pick up as well. For more difficult waste, they have containers where people can dispose of construction waste, asphalt shingles, concret, and garden waste such as rocks and dirt. In Quebec there are a couple of cement kilns that use asphalt shingles and other similar waste for energy. There is alos a hazardous waste depot which is run on a regular basis.

They are looking at reducing GHG emissions. They have restricted water use and promote water conservation and for people to be ecologically responsible. They also require permits for tree removal and pesticide application. This gives the council control over the trees and pesticide use. They promote pesticide use as a last resource.

Finally what impressed me is that they have a green line that citizens can call if they have questions and problems that they can't solve. This green line gives them access to an environmental/ecological consultant who can help them with their problems and even visit the citizen's site of concern. Not only does this help citizens but it presents a good opportunity to educate and sensitize the citizens about environmental solutions and how precious the environment is.

In any case, in looking at the town, I can understand why they were able to embrace the sustainable transportation project. As well there is a strong sense of community, which should help any one moving there to fit in as there are a number of events that they can participate in. THe train station idea also gives the locals a feasible option to stay in the community that they love and still work in Montreal.

Sara

- Log in to post comments

Who was the spear head

Although I would still like to know who planted the seed for the sustainable transportation system.

- Log in to post comments

An advanced town

Hi Sara,

Are you referring to the environmental bulletin that I showed you in our meeting on Sunday? I believe it is in French so not accessible to all in the group.

Dr. Ling - Please note that available background documentation that I found is in French.

GS

- Log in to post comments

Mobility HUBs, Toronto, Ontario

Mobility HUBs, Toronto, OntarioLevi Waldron

Published January 21, 2007

Case Summary

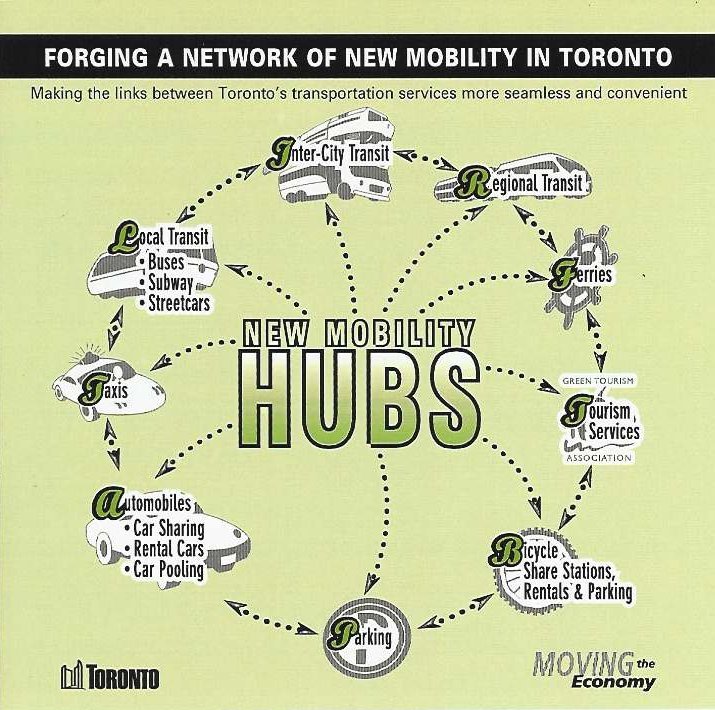

A transit route is only as good as its weakest link, and potential users may be lost because of a lack of options at the beginning or end of their potential route, or by the cost and inconvenience of changing transit systems across municipal boundaries. The concept behind the New Mobility HUB project is to fill in these gaps with a network of hubs across Toronto, which conveniently link multiple modes of sustainable transportation. The Exhibition Place New Mobility HUB is the first site of the project, located where GO Train service between downtown and the suburbs and three local Toronto transit lines converge. Launched in April 2006 by the partnership Moving the Economy (MTE), this hub added short and long-term bicycle storage, a BikeShare station, Autoshare car sharing, a taxi hotline, wireless hotspot, and bicycle and transit route maps.

Figure 1: The New Mobility HUB concept (Moving the Economy, 2006)

Sustainable Development Characteristics